Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ammonia Gas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Al2O3 Hollow Fiber Membranes

2.3. Preparation of Undoped TiO2 and N-TiO2 Photocatalyst Powders

2.4. Preparation of Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Undoped TiO2 and N-TiO2 Photocatalysts

2.5. Characterization of Undoped TiO2 and N-TiO2 Photocatalyst Powders and Deposited Films

2.6. Photocatalytic Degradation of Gaseous Ammonia

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Al2O3 Hollow Fiber Membranes

3.2. Characterization of Undoped TiO2 and N-TiO2 Photocatalyst Powders

3.3. Characterization of Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Undoped TiO2 and N-TiO2 Photocatalysts

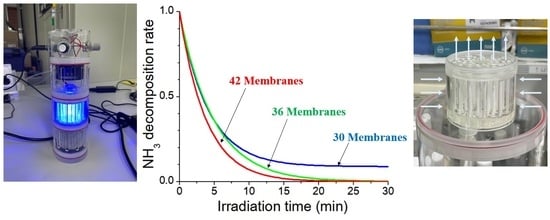

3.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Test of Gaseous Ammonia

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koci, K.; Reli, M.; Troppova, I.; Prostejovsky, T.; Zebrak, R. Degradation of ammonia from gas stream by advanced oxidation processes. J. Environ. Sci. Health-Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng 2020, 55, 433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C.; Sutton, M.C.; Oenema, O.; Bittman, S. Costs of ammonia abatement: Summary, conclusions and policy context. In Costs of Ammonia Abatement and the Climate Co-Benefits; Reis, S., Howard, C., Sutton, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, M.-S.; Wang, C.-H. Treatment of ammonia in air stream by biotrickling filter. Aerosol Air. Qual. Res. 2007, 7, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakar, S.A.; Ribeiro, C. Nitrogen-doped titanium dioxide: An overview of material design and dimensionality effect over modern applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev. 2016, 27, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.J.; Wang, X.K.; Tang, S.F. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation kinetic of gaseous ammonia over nano-TiO2 supported on latex paint film. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2008, 21, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopyan, I. Kinetic analysis on photocatalytic degradation of gaseous acetaldehyde, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide on nanosized porous TiO2 films. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2007, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Yu, H.; Gao, X.Q. Degradation of indoor ammonia using TiO2 thin film doped with Iron (III) under visible light illumination. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 668, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zendehzaban, M.; Sharifnia, S.; Hosseini, S.N. Photocatalytic degradation of ammonia by light expanded clay aggregate (LECA)-coating of TiO2 nanoparticles. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, S. Photocatalytic degradation of ammonia-nitrogen via N-doped graphene/bismuth sulfide catalyst under near-infrared light irradiation. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2021, 4, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Chen, Z.Y.; Bao, S.J.; Wang, M.Q.; Song, C.L.; Pu, S.; Long, D. Ultrafine TiO2 encapsulated in nitrogen-doped porous carbon framework for photocatalytic degradation of ammonia gas. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 331, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čižmar, T.; Grčić, I.; Bohač, M.; Razum, M.; Pavić, L.; Gajović, A. Dual use of copper-modified TiO2 nanotube arrays as material for photocatalytic NH3 degradation and relative humidity sensing. Coatings 2021, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakre, P.V.; Tilve, S.G.; Shirsat, R.N. Influence of N sources on the photocatalytic activity of N-doped TiO2. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 7637–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Shahzad, A.; Farooq, A.; Kamran, M.; Ud-Din Khan, S. Thermal analysis in swirling flow of titanium dioxide–aluminum oxide water hybrid nanofluid over a rotating cylinder. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 144, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Magnone, E.; Park, J.H. Preparation, characterization and laboratory-scale application of modified hydrophobic aluminum oxide hollow fiber membrane for CO2 capture using H2O as low-cost absorbent. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 494, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnone, E.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.H. Relationships between electroless plating temperature, Pd film thickness and hydrogen separation performance of Pd-coated Al2O3 hollow fibers. Mater. Lett. 2020, 272, 127811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Pak, S.H.; Shin, M.C.; Park, C.-G.; Magnone, E.; Park, J.H. Development of an advanced hybrid process coupling TiO2 photocatalysis and zeolite-based adsorption for water and wastewater treatment. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 36, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Anpo, M. Synthesis and characterization of nitrogen-doped TiO2 nanophotocatalyst with high visible light activity. J. Phys. Chem. 2007, 111, 6976–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, Y.; Kılıç, M.; Çınar, Z. The role of non-metal doping in TiO2 photocatalysis. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2010, 13, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackley, V.A.; Stefaniak, A.B. “Real-world” precision, bias, and between-laboratory variation for surface area measurement of a titanium dioxide nanomaterial in powder form. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Z.; Dong, F.; Zhao, W.; Guo, S. Visible light induced electron transfer process over nitrogen doped TiO2 nanocrystals prepared by oxidation of titanium nitride. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myilsamy, M.; Mahalakshmi, M.; Murugesan, V.; Subha, N. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of nitrogen and indium co-doped mesoporous TiO2 nanocomposites for the degradation of 2,4-dinitrophenol under visible light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 342, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Liu, B.; Lei, Z.; Sun, J. Structure and photoluminescence of the TiO2 films grown by atomic layer deposition using tetrakis-dimethylamino titanium and ozone. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liqiang, J.; Yichun, Q.; Baiqi, W.; Shudan, L.; Baojiang, J.; Libin, Y.; Wei, F.; Hongganga, F.; Jiazhong, S. Review of photoluminescence performance of nano-sized semiconductor materials and its relationships with photocatalytic activity. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2006, 90, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azri, Z.H.N.; Chen, W.-T.; Chan, A.; Jovic, V.; Ina, T.; Idriss, H.; Waterhouse, G.I.N. The roles of metal co-catalysts and reaction media in photocatalytic hydrogen production: Performance evaluation of M/TiO2 photocatalysts (M = Pd, Pt, Au) in different alcohol–water mixtures. J. Catal. 2015, 329, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, Q.; Hou, Q.; Wei, L.; Liu, L.; Huang, F.; Ju, M. Enhancement of photocatalytic performance with the use of noble-metal-decorated TiO2 nanocrystals as highly active catalysts for aerobic oxidation under visible-light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. 2017, 210, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G.; Pistarino, C. Abatement of ammonia and amines from waste gases: A summary. J. Loss. Prev. Process. Ind. 2003, 16, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Band Gap Energy (eV) | Element Amount (at.%) | BET Surface Area (m2g−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | O | N | |||

| Pure TiO2 | 3.17 | 26.4 | 73.6 | - | 50 |

| N-doped TiO2 | 2.36 | 27.9 | 69.2 | 2.9 | 57 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magnone, E.; Hwang, J.Y.; Shin, M.C.; Zhuang, X.; Lee, J.I.; Park, J.H. Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ammonia Gas. Membranes 2022, 12, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12070693

Magnone E, Hwang JY, Shin MC, Zhuang X, Lee JI, Park JH. Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ammonia Gas. Membranes. 2022; 12(7):693. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12070693

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagnone, Edoardo, Jae Yeon Hwang, Min Chang Shin, Xuelong Zhuang, Jeong In Lee, and Jung Hoon Park. 2022. "Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ammonia Gas" Membranes 12, no. 7: 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12070693

APA StyleMagnone, E., Hwang, J. Y., Shin, M. C., Zhuang, X., Lee, J. I., & Park, J. H. (2022). Al2O3-Based Hollow Fiber Membranes Functionalized by Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Dioxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ammonia Gas. Membranes, 12(7), 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12070693