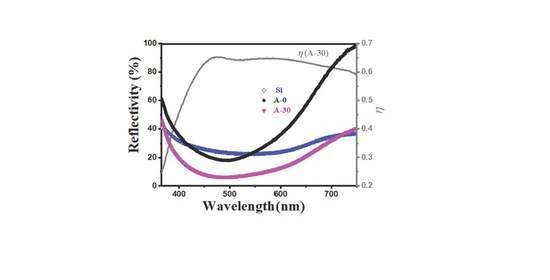

Ultra-Low Reflectivity in Visible Band of Vanadium Alumina Nanocomposites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experiments

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.G.; Yu, K.; Gong, S.J.; Du, E.; Zhu, Z.Q. Vanadium based carbide–oxide heterogeneous V2O5@V2C nanotube arrays for high-rate and long-life lithium–sulfur batteries. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 18950–18964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K.I.; Song, S.A.; Kim, S.S. Glucose-based carbon-coating layer on carbon felt electrodes of vanadium redox flow batteries. Compos. Part B 2019, 175, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulou, M.; Vernardou, D.; Koudoumas, E.; Tsoukalas, D.; Raptis, Y.S. Oxygen and temperature effects on the electrochemical and electrochromic properties of rf-sputtered V2O5 thin films. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 232, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain, E.E. Optical properties of vanadium dioxide and vanadium pentoxide thin films. Appl. Opt. 1991, 30, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.B.; Zuo, D.W.; Lu, W.Z. Influence of film thickness on structural and optical-switching properties of vanadium pentoxide films. Surf. Eng. 2016, 33, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Q.; Wang, S.Y.; Hu, Z.Y.; Lou, D.M. Durability of V2O5-WO3/TiO2 selective catalytic reduction catalysts for heavy-duty diesel engines using B20 blend fuel. Energy 2019, 179, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlamova, T.S.; Urazov, K.K.; Vodyankina, O.V. Effect of Modification of Supported V2O5/SiO2 Catalysts by Lanthanum on the State and Structural Peculiarities of Vanadium. Kinet. Catal. 2019, 60, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, C.L. The split-off terahertz radiating dipoles on thermally reduced α-V2O5 (001) surface. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 21368–21375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, M.F.; Lee, D.W.; Rehman, M.A.; Seo, Y.; Lee, S.H. Vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) as an antireflection coating for graphene/silicon solar cell. Mat. Sci. Semicon. Proc. 2018, 86, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, L.E.; Tkachenko, O.P.; Guraya, M.; Gao, X.; Wachs, I.E.; Wolfgang, G. Surface-Analytical Studies of Supported Vanadium Oxide Monolayer Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 4823–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañares, M.A.; Martínez-Huerta, M.; Gao, X.; Wachs, I.E.; Fierro, J.L.G. Identification and roles of the different active sites in supported vanadia catalysts by in situ techniques. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2000, 130, 3125–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Dai, B.; Xia, F.; Wang, P.; Guo, S.; Gao, G.; Xu, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Evolution of structures and optical properties of vanadium oxides film with temperature deposited by magnetron sputtering. Infrared. Phys. Techn. 2020, 107, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, N.; Zuo, D.; Lu, W.; Xing, Y. Electrical and optical properties of vanadium pentoxide nano-thin films with different substrate polishing processes. Ferroelectrics 2019, 551, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, S.W.; Ryu, J.W.; Xu, Y.; Kato, R. Optical and Thermal Properties of V2O5 Thin Films with Crystallization. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2013, 62, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Kulkarni, N.; Kaur, D. Structural and optical studies of nanocrystalline V2O5 thin films. Thin. Solid. Film. 2008, 516, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tang, W.; Ji, L.; Chen, S. V2O5/Al2O3 composite photocatalyst: Preparation, characterization, and the role of Al2O3. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 180, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, A.; Vijayan, V.; Kumar, S.D.; Sankar, L.P.; Parthipan, N.; Tafesse, D.; Tufa, M. Parameters of Porosity and Compressive Strength-Based Optimization on Reinforced Aluminium from the Recycled Waste Automobile Frames. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 3648480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, J.S.; Alrowaili, Z.A.; Saleh, H.H.; Hammoud, A.; Alomairy, S.; Sriwunkum, C.; Al-Buriahi, M.S. Synthesis, physical and nuclear shielding properties of novel Pb-Al alloys. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 2021, 142, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Hessien, M.; Alresheedi, F.; Al-Baradi, A.M.; Alrowaili, Z.A.; Kebaili, I.; Olarinoye, I.O. ZnO-Bi2O3 nanopowders: Fabrication, structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 3464–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrowaili, Z.A.; Taha, T.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Saron, K.M.A.; Sriwunkum, C.; Al-Baradi, A.M.; Al-Buriahi, M.S. Synthesis and characterization of B2O3-Ag3PO4-ZnO-Na2O glasses for optical and radiation shielding applications. Optik 2021, 248, 168199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrowaili, Z.A.; Ali, A.M.; Al-Baradi, A.M.; Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Wahab, E.A.A.; Shaaban, K.S. A significant role of MoO3 on the optical, thermal, and radiation shielding characteristics of B2O3–P2O5–Li2O glasses. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2022, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.I.; Kim, I.K.; Oh, E.J.; Kim, S.W.; Ryu, J.W.; Park, H.Y. Dependence of optical properties of vanadium oxide films on crystallization and temperature. Thin. Solid. Film. 2012, 520, 2368–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.C. Angular distribution of hybridization in sputtered carbon thin film. AIP. Adv. 2017, 7, 085303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, O.; Uegaki, T.; Miyata, Y.; Shimizu, K. Formation of AlVO4 Solid Solution from Alkoxides. J. Am. Ceram Soc. 1987, 70, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyer, B.; Schmelz, H.; Gobel, H.; Meixner, H.; Scherg, T.; Knozinger, H. Preparation of AlVO4-films for sensor application via a sol-gel/spin-coating technique. Thin. Solid. Film. 1997, 310, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, G.K.; Butler, M.A.; West, K.W.; Buchanan, D.N.E. Determination of the Gaussian and Lorentzian content of experimental line shapes. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1974, 45, 1369–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, L.E.; Jehng, J.M.; Cornaglia, L.; Hirt, M.A.; Wachs, I.E. Quantitative determination of the number of surface active sites and the turnover frequency for methanol oxidation over bulk metal vanadates. Catal Toda. 2003, 78, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, G. Co-Assembled Supported Catalysts: Synthesis of Nano-Structured Supported Catalysts with Hierarchic Pores through Combined Flow and Radiation Induced Co-Assembled Nano-Reactors. Catalysts 2016, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, G. Plasma Generating-Chemical Looping Catalyst Synthesis by Microwave Plasma Shock for Nitrogen Fixation from Air and Hydrogen Production from Water for Agriculture and Energy Technologies in Global Warming Prevention. Catalysts 2020, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hogan, C.J., Jr. Nanoparticle Dynamics in the Spatial Afterglows of Nonthermal Plasma Synthesis Reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K.; Katsufuji, T.; Mori, S.; Nohara, M.; Machida, A.; Moritomo, Y.; Kato, K.; Nishibori, E.; Takata, M.; Sakata, M.; et al. Charge Ordering and Spin Frustration in AlV2-xCrxO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 096404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horibe, Y.; Kurushima, K.; Mori, S. Doping effect on the charge ordering in AlV2O4. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 052411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.H.; Jiang, P.; Jiang, B. Broadband moth-eye antireflection coatings on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 061112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermadi, S.; Agoudjil, N.; Sali, S.; Tala-lghil, R.; Boumaour, M. Sol-gel Synthesis of SiO2-TiO2 film as antireflection coating on silicon for photovoltaic application. Mater. Sci. Forum 2009, 609, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Chen, X. Recent progress of nanomaterials for microwave absorption. J. Mater. 2019, 5, 503–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Wang, H. Ultra-Low Reflectivity in Visible Band of Vanadium Alumina Nanocomposites. Coatings 2022, 12, 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12091276

Wang Q, Zhao G, Wang H. Ultra-Low Reflectivity in Visible Band of Vanadium Alumina Nanocomposites. Coatings. 2022; 12(9):1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12091276

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiujin, Guozhong Zhao, and Hai Wang. 2022. "Ultra-Low Reflectivity in Visible Band of Vanadium Alumina Nanocomposites" Coatings 12, no. 9: 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12091276

APA StyleWang, Q., Zhao, G., & Wang, H. (2022). Ultra-Low Reflectivity in Visible Band of Vanadium Alumina Nanocomposites. Coatings, 12(9), 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12091276