Investigating Plant Micro-Remains Embedded in Dental Calculus of the Phoenician Inhabitants of Motya (Sicily, Italy)

Abstract

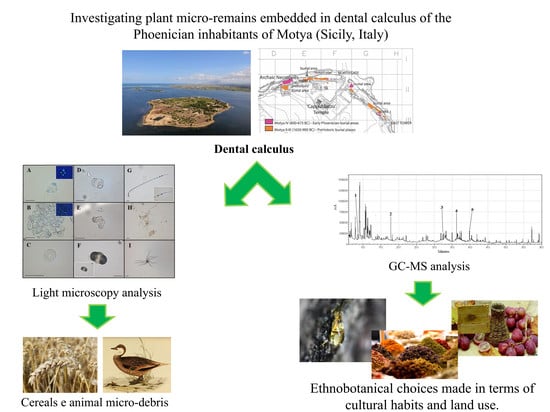

:1. Introduction

Archaeological and Historical Context

2. Results

2.1. Optical Microscopy (OM) Analysis

2.1.1. Starch Granules

2.1.2. Pollen

2.1.3. Other Plant Micro-Remains

2.1.4. Animal Micro-Debris

2.2. Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Dental Calculus Collection

4.2. Decontamination and Sterilization Protocols

4.3. OM Analysis.

4.4. GC-MS Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OM | Optical microscopy |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography mass spectrometry |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

References

- Henry, A.G.; Piperno, D.R. Using plant microfossils from dental calculus to recover human diet: A case study from Tell al-Raqā’i, Syria. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.C.; Salazar-García, D.C.; Wittig, R.M.; Freiberg, M.; Henry, A.G. Dental calculus evidence of Taï Forest chimpanzee plant consumption and life history transitions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, D.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Cao, Y.; Sun, K.; Jin, S.A. Starch grain analysis of human dental calculus to investigate Neolithic consumption of plants in the middle Yellow River Valley, China: A case study on Gouwan site. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2015, 2, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiani, E.; Radini, A.; Edinborough, M.; Borić, D. Dental calculus reveals Mesolithic foragers in the Balkans consumed domesticated plant foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10298–10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Power, R.C.; Salazar-García, D.C.; Rubini, M.; Darlas, A.; Havarti, K.; Walker, M.; Hublin, J.J.; Henry, A.G. Dental calculus indicates widespread plant use within the stable Neanderthal dietary niche. J. Hum. Evol. 2018, 119, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hardy, K.; Radini, A.; Buckley, S.; Sarig, R.; Copeland, L.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. Dental calculus reveals potential respiratory irritants and ingestion of essential plant-based nutrients at Lower Palaeolithic Qesem cave Israel. Quat. Int. 2015, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radini, A.; Nikita, E.; Buckley, S.; Copeland, L.; Hardy, K. Beyond food: The multiple pathways for inclusion of materials into ancient dental calculus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2017, 162, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radini, A.; Tromp, M.; Beach, A.; Tong, E.; Speller, C.; McCormick, M.; Dudgeon, J.V.; Collins, M.J.; Rühli, F.R.; Kröger, R.; et al. Medieval women’s early involvement in manuscript production suggested by lapis lazuli identification in dental calculus. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Agostino, A.; Gismondi, A.; Di Marco, G.; Lo Castro, M.; Olevano, R.; Cinti, T.; Leonardi, D.; Canini, A. Lifestyle of a Roman Imperial community: Ethnobotanical evidence from dental calculus of the Ager Curensis inhabitants. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorin, E.; Sáez, L.; Malgosa, A. Ferns as healing plants in medieval Mallorca, Spain? Evidence from human dental calculus. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2019, 29, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, A.G.; Brooks, A.S.; Piperno, D.R. Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hardy, K.; Buckley, S.; Collins, M.J.; Estalrrich, A.; Brothwell, D.; Copeland, L.; García-Tabernero, A.; García-Vargas, S.; de la Rasilla, M.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; et al. Neanderthal medics? Evidence for food, cooking, and medicinal plants entrapped in dental calculus. Naturwissenschaften 2012, 99, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, S.; Usai, D.; Jakob, T.; Radini, A.; Hardy, K. Dental calculus reveals unique insights into food items, cooking and plant processing in prehistoric central Sudan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cristiani, E.; Radini, A.; Borić, D.; Robson, H.K.; Caricola, I.; Carra, M.; Mutri, G.; Oxilia, G.; Zupancich, A.; Šlaus, M.; et al. Dental calculus and isotopes provide direct evidence of fish and plant consumption in Mesolithic Mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, L.S.; Yost, C.; Sołtysiak, A. Plant microfossils in human dental calculus from Nemrik 9, a pre-pottery Neolithic site in northern Iraq. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2018, 10, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gismondi, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Di Marco, G.; Martínez-Labarga, C.; Leonini, V.; Rickards, O.; Canini, A. Back to the roots: Dental calculus analysis of the first documented case of coeliac disease. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieverse, A.R. Diet and the aetiology of dental calculus. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 1999, 9, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, C.; Vashro, L.; O’Connell, J.F.; Henry, A.G. Plant microremains in dental calculus as a record of plant consumption: A test with Twe forager-horticulturalists. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2015, 2, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, R.C.; Salazar-García, D.C.; Straus, L.G.; Morales, M.R.G.; Henry, A.G. Microremains from El Mirón Cave human dental calculus suggest a mixed plant–animal subsistence economy during the Magdalenian in Northern Iberia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozga, A.T.; Nieves-Colón, M.A.; Honap, T.P.; Sankaranarayanan, K.; Hofman, C.A.; Milner, G.R.; Lewis, C.M., Jr.; Stone, A.C.; Warinner, C. Successful enrichment and recovery of whole mitochondrial genomes from ancient human dental calculus. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop. 2016, 160, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendy, J.; Warinner, C.; Bouwman, A.; Collins, M.J.; Fiddyment, S.; Fischer, R.; Hagan, R.; Hofman, C.A.; Holst, M.; Chaves, E.; Klaus, L.; et al. Proteomic evidence of dietary sources in ancient dental calculus. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20180977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercader, J.; Akeju, T.; Brown, M.; Bundala, M.; Collins, M.J.; Copeland, L.; Crowther, A.; Dunfield, P.; Henry, A.; Inwood, J.; et al. Exaggerated expectations in ancient starch research and the need for new taphonomic and authenticity criteria. Facets 2018, 3, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stika, H.P.; Heiss, A.G.; Zach, B. Plant remains from the early Iron Age in western Sicily: Differences in subsistence strategies of Greek and Elymian sites. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2008, 17, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnoux, C.; Celant, A.; Coubray, S.; Fiorentino, G.; Zech-Matterne, V. The introduction of Citrus to Italy, with reference to the identification problems of seed remains. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2013, 22, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucchesu, M.; Sarigu, M.; Del Vais, C.; Sanna, I.; d’Hallewin, G.; Grillo, O.; Bacchetta, G. First finds of Prunus domestica L. in Italy from the Phoenician and Punic periods (6th–2nd centuries bc). Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2017, 26, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgado, A.; Ferrer, M. Cultural contacts in colonial settings: The construction of new identities in Phoenician settlements of the Western Mediterranean. Stanf. J. Archaeol. 2007, 5, 18–42. [Google Scholar]

- Aubet, M.A. Phoenicia during the Iron Age II period. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant; Steiner, M.L., Killebrew, A.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 707–716. [Google Scholar]

- Orendi, A.; Deckers, K. Agricultural resources on the coastal plain of Sidon during the Late Iron Age: Archaeobotanical investigations at Phoenician Tell el-Burak, Lebanon. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2018, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasca, A. Scavi alle mura di Mozia (campagna 1976). Riv. Studi Fenici 1977, 5, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli, F. Sepolture intramurali a Mozia. Scienze dell’Antichità, vol. 14, Sepolti tra i vivi. Buried among the living. In Proceedings of the Evidenza ed Interpretazione di Contesti Funerari in Abitato, Museo dell’Arte Classica, Odeion, Boston, MA, USA, 26–29 April 2006; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, P. Morte e società a Mozia. Ipotesi preliminari sulla base della documentazione archeologica della necropoli. Römische Mitt. 2013, 119, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ciasca, A. Sulle necropoli di Mozia. Sicil. Archeol. 1990, 23, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ciasca, A. Sulle mura di Mozia. In Studi sulla Sicilia Occidentale in onore di Vincenzo Tusa; La Genière, J., Ed.; Bottega d’Erasmo: Turin, Italy, 1993; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, L.; Spagnoli, F. Landing on Motya. In The Earliest Phoenician Settlement of the 8th Century BC and the Creation of a West Phoenician Cultural Identity in the Excavations of Sapienza University of Rome-2012–2016. Stratigraphy, Architecture, and Finds; Quaderni di Archeologia Fenicio-Punica, Missione archeologica a Mozia: Roma, Italy, 2017; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- ICSN. The International Code for Starch Nomenclature. Available online: http://fossilfarm.org/ICSN/Code.html 2011 (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Gismondi, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Canuti, L.; Di Marco, G.; Basoli, F.; Canini, A. Starch granules: A data collection of 40 food species. Plant Biosyst. 2019, 153, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grímsson, F.; Zetter, R. Combined LM and SEM study of the middle Miocene (Sarmatian) palynoflora from the Lavanttal Basin, Austria: Part II. Pinophyta (Cupressaceae, Pinaceae and Sciadopityaceae). Grana 2011, 50, 262–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, A.C.; Harvey, W.J. The Global Pollen Project: A new tool for pollen identification and the dissemination of physical reference collections. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017, 8, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PalDat a Palynological Database. 2000. Available online: http://www.paldat.org (accessed on 19 May 2019).

- Adedeji, O.; Dloh, H.C. Comparative foliar anatomy of ten species in the genus Hibiscus Linn, in Nigeria. New Bot. 2004, 31, 147–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bondada, B.R.; Oosterhuis, D.M. Comparative epidermal ultrastructure of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) leaf, bract and capsule wall. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschan, G.F.; Denk, T. Trichome types, foliar indumentum and epicuticular wax in the Mediterranean gall oaks, Quercus subsection Galliferae (Fagaceae): Implications for taxonomy, ecology and evolution. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 169, 611–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lippi, M.M.; Secci, M.M.; Giachi, G.; Bouby, L.; Terral, J.F.; Castiglioni, E.; Cottini, M.; Rottoli, M.; de Grummond, N.T. Plant remains in an Etruscan-Roman well at Cetamura del Chianti, Italy. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, C.J.; Koch, S.L. Microscopy of feathers: A practical guide for forensic feather identification. Microscope-Chicago 2011, 59, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Eglinton, G.; Hamilton, R.J.; Raphael, R.A.; Gonzalez, A.G. Hydrocarbon constituents of the wax coatings of plant leaves: A taxonomic survey. Phytochemistry 1962, 1, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, S.A.; Stott, A.W.; Evershed, R.P. Studies of organic residues from ancient Egyptian mummies using high temperature-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and sequential thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Analyst 1999, 124, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, S.; Tocheri, M.W.; Sutikna, T.; Saptomo, E.W.; Roberts, R.G. Incorporating terpenes, monoterpenoids and alkanes into multiresidue organic biomarker analysis of archaeological stone artefacts from Liang Bua (Flores, Indonesia). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 19, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkens, J. The preservation and identifcation of piñon resins by GC-MS in pottery from the western Great Basin. Archaeometry 2002, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonasera, T. Investigating the presence of ancient absorbed organic residues in groundstone using GC–MS and other analytical techniques: A residue study of several prehistoric milling tools from central California. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, S.; Hayes, E.; Flannery, E.; Sutikna, T.; Tocheri, M.W.; Saptomo, E.W.; Roberts, R.G. Development and application of a comprehensive analytical workflow for the quantification of non-volatile low molecular weight lipids on archaeological stone tools. Anal. Met. 2017, 9, 4349–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evershed, R.P. Chemical composition of a bog body adipocere. Archaeometry 1992, 34, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, J.; Jervis, B.; De Vos, D.; Waelkens, M. Molecular evidence for the mixing of Meat, Fish and Vegetables in Anglo-Saxon coarseware from Hamwic, UK. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 1150–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudinas, B.; Villoutrei, J. Fatty acid methyl esters in photosynthetic bacteria. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 1299–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkens, J.W. GC-MS analysis and fatty acid ratios of archaeological potsherds from the western great basin of North America. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passi, S.; Cataudella, S.; Di Marco, P.; De Simone, F.; Rastrelli, L. Fatty acid composition and antioxidant levels in muscle tissue of different Mediterranean marine species of fish and shellfish. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7314–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.; Block, R.; Mousa, S.A. Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: Health benefits throughout life. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Guang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. An overview on biological production of functional lactose derivatives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3683–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juteau, F.; Masotti, V.; Bessière, J.M.; Viano, J. Compositional characteristics of the essential oil of Artemisia campestris var. Glutinosa. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2002, 30, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golparvar, A.R.; Hadipanah, A.; Mehrabi, A.M. Diversity in chemical composition from two ecotypes of (Mentha longifolia L.) and (Mentha spicata L.) in Iran climatic conditions. JBES 2015, 6, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Essien, E.E. Stem volatile oils composition of Ocimum basilicum L. cultivars and Ocimum gratissimum L. from Nigeria. Am. J. Essent. 2018, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bettaieb, I.; Bourgou, S.; Ben Kaab, S.; Aidi Wannes, W.; Ksouri, R.; Saidini Tounsi, M.; Fauconnier, M.L. On the effect of initial drying techniques on essential oil composition, phenolic compound and antioxidant properties of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) seeds. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 284, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colombini, M.P.; Giachi, G.; Modugno, F.; Ribechini, E. Characterisation of organic residues in pottery vessels of the Roman age from Antinoe (Egypt). Microchem. J. 2005, 79, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribechini, E.; Orsini, S.; Silvano, F.; Colombini, M.P. Py-GC/MS, GC/MS and FTIR investigations on LATE Roman-Egyptian adhesives from opus sectile: New insights into ancient recipes and technologies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 638, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerković, I.; Marijanović, Z.; Gugić, M.; Roje, M. Chemical profile of the organic residue from ancient amphora found in the Adriatic Sea determined by direct GC and GC-MS analysis. Molecules 2011, 16, 7936–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigenberger, G.; Herm, C. Natural resins and balsams from an eighteenth-century pharmaceutical collection analysed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, A.; Oshima, Y.; Hikino, H. Spirojatamol, a new skeletal sesquiterpenoid of Nardostachys jatamansi roots. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyal, P.; Chhetri, B.K.; Dosoky, N.S.; Poudel, A.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical Composition of Nardostachys grandiflora Rhizome Oil from Nepal–A Contribution to the Chemotaxonomy and Bioactivity of Nardostachys. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hikino, H.; Sakurai, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Takemoto, T. Structure of curdione. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1967, 15, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mau, J.L.; Lai, E.Y.; Wang, N.P.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.H.; Chyau, C.C. Composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil from Curcuma zedoaria. Food Chem. 2003, 82, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venskutonis, P.R.; Dagilyte, A. Composition of essential oil of sweet flag (Acorus calamus L.) leaves at different growing phases. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, N.M.; Ha, V.T.; Khanh, P.N.; Van, D.T.; Cuong, T.D.; Huong, T.T.; Thuy, D.T.T.; Nhan, N.T.; Hanh, N.P.; Toan, T.Q.; et al. Chemical compositions and antimicrobial activity of essential oil from the rhizomes of Curcuma singularis growing in Vietnam. Am. J. Essent. 2017, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bakels, C. Plant remains from Sardinia, Italy with notes on barley and grape. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2002, 11, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, E.M.M.; Castro, J.L.L.; Ferjaoui, A.; Martín, A.M.; Hahnmüller, V.M.; Jerbania, I.B. First carpological data of the 9th century BC from the Phoenician city of Utica (Tunisia). In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop for African Archaeobotany, Modena and Reggio Emilia, IWAA8, Italy, 23–26 June 2015; p. 146.

- Woolmer, M. A Short History of the Phoenicians; Tauris, I.B., Ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bisi, A.M. I commerci fenici tra Oriente ed Occidente (nuove prospettive di metodo e nuovi tempi di indagine). Studi Urbinati B/3 1986, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburello, I. Materiali per una Storia Dell’Economia Della Sicilia Punica; Atti del II Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici I: Roma, Italy, 1991; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburello, I. Il paesaggio rurale dell’area elima. In Gli Elimi e l’Area Elima Fino All’Inizio Della Prima Guerra Punica. Atti del Seminario di Studi, Palermo—Contessa Entellina—25–28 Maggio 1989; Società siciliana per la storia patria: Palermo, Italy, 1990; pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, L.; Hardy, K. Archaeological starch. Agronomy 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazzola, A.; Bergamasco, A.; Calvo, S.; Caruso, G.; Chemello, R.; Colombo, F.; Giaccone, G.; Gianguzza, P.; Guglielmo, L.; Leonardi, M.; et al. Sicilian transitional areas: State of the art and future development. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 26, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, L. Mozia-XI. Il Tempio del Kothon. Rapporto preliminare delle campagne di scavi XXIII e XXIV (2003–2004) Condotte Congiuntamente Con Il Servizio Beni Archeologici della Soprintendenza Regionale per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali di Trapani; Quaderni di Archeologia Fenicio-Punica, II Missione archeologica a Mozia: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli, F. Ritual Practices, Food Offerings, and Animal Sacrifices: Votive Deposits of the Temple of the Kothon (Motya). In Religious Convergence in the Ancient Mediterranean; Blakely, S., Collins, B.J., Eds.; Lockwood Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar]

- Lardos, A.; Prieto-Garcia, J.; Heinrich, M. Resins and gums in historical iatrosophia texts from Cyprus—A botanical and medico-pharmacological approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robbat, A., Jr.; Kowalsick, A.; Howell, J. Tracking juniper berry content in oils and distillates by spectral deconvolution of gas chromatography/mass spectrometry data. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 5531–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liphshitz, N.; Bigger, G. Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani). Isr. Explor. J. 1991, 41, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, A. From the hills of Adonis through the Pillars of Hercules: Recent advances in the archaeology of Canaan and Phoenicia. Near East Archaeol. 2002, 65, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Mariette, S.; Lefèvre, F.; Fady, B.; Grenier-de March, G.; Plomion, C.; Savouré, A. Geographical diversity and genetic relationships among Cedrus species estimated by AFLP. Tree Genet. Genomes 2007, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, Y.; Kaçar, M.S.; Isik, K. Traditional tar production from Cedrus libani A. Rich on the Taurus Mountains in southern Turkey. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabato, D.; Peña-Chocarro, L.; Ucchesu, M.; Sarigu, M.; Del Vais, C.; Sanna, I.; Bacchetta, G. New insights about economic plants during the 6th–2nd centuries bc in Sardinia, Italy. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2019, 28, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, L.; Spagnoli, F. Alle Sorgenti del Kothon. Il Rito a Mozia Nell’Area Sacra di Baal ‘Addir-Poseidon. Lo Scavo dei Pozzi Sacri Nel Settore C Sud-Ovest (2006–2011); Quaderni di Archeologia Fenicio-Punica, Missione archeologica a Mozia: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, L.; Spagnoli, F. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) from Motya and its deepest oriental roots. Vicino Oriente XXII 2018, 49–90. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.; Villate, E.; Bernúz, M. Palaeoecological analysis of the sedimentary remains from the Phoenicia necropolis. The Phoenician cemetery of Tyre Al-Bass. Excavations 1997, 1999, 220–246. [Google Scholar]

- Estreicher, S.K. Wine: From Neolithic Times to the 21st Century; Algora Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.G. The Grapevine, Viticulture, and Winemaking: A Brief Introduction. In Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pecci, A.; Giorgi, G.; Salvini, L.; Ontiveros, M.Á.C. Identifying wine markers in ceramics and plasters using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Experimental and archaeological materials. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.; Jalabadze, M.; Batiuk, S.; Callahan, M.P.; Smith, K.E.; Hall, G.R.; Kvavadze, E.; Maghradze, D.; Rusishvili, N.; Bouby, L.; et al. Early Neolithic wine of Georgia in the South Caucasus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10309–E10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sochorova, L.; Torokova, L.; Baron, M.; Sochor, J. Electrochemical and others techniques for the determination of malic acid and tartaric acid in must and wine. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 9145–9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H. (n-3) fatty acids and cardiovascular health: Are effects of EPA and DHA shared or complementary? J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garnier, N.; Bernal-Casasola, D.; Driard, C.; Pinto, I.V. Looking for Ancient Fish Products through Invisible Biomolecular Residues in the Roman Production Vats from the Atlantic Coast. J. Marit. Archaeol. 2018, 13, 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, E.A.; Hart, J.P. Pine resins and pottery sealing: Analysis of absorbed and visible pottery residues from central New York State. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carenti, G. Sant’Antioco (SW Sardinia, Italy): Fish and fishery resource exploitation in a western Phoenician Colony. Archaeofauna 2013, 22, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Di Natale, A. The ancient distribution of bluefin tuna fishery: How coins can improve our knowledge. Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. 2014, 70, 2828–2844. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, A.; Petersen, H. Murex-Purple Dye: The Archaeology behind the Production and an Overview of Sites in the Northwest Maghreb Region. Master’s Thesis, Maritime Archaeology University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, Denmark, 15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veen, M.; Morales, J. The Roman and Islamic spice trade: New archaeological evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 167, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staub, P.O.; Casu, L.; Leonti, M. Back to the roots: A quantitative survey of herbal drugs in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica (ex Matthioli, 1568). Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnima, B.M.; Kothiyal, P. A review article on phytochemistry and pharmacological profiles of Nardostachys jatamansi DC-medicinal herb. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2015, 3, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Motley, T.J. The ethnobotany of sweet flag, Acorus calamus (Araceae). Econ. Bot. 1994, 48, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Malviya, R. Pharmacological properties and ayurvedic value of Indian buch plant (Acorus calamus): A short review. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2011, 5, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.L.; Yu, Y.; Qin, D.P.; Gao, H.; Yao, X.S. Acorus Linnaeus: A review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and neuropharmacology. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 5173–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, K.C.; Dikshit, N.; Nizar, M.A. Ethnobotany of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2012, 11, 607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Moricca, C.; Nigro, L.; Sadori, L. Botany meets archaeology: Archaeobotany at Motya (Italy). In Proceedings of the Le Scienze e i Beni Culturali: Innovazione e Multidisciplinarietà, Milano, Italy, 26 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, A.; Haslam, M.; Oakden, N.; Walde, D.; Mercader, J. Documenting contamination in ancient starch laboratories. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, A.; Di Marco, G.; Martini, F.; Sarti, L.; Crespan, M.; Martínez-Labarga, C.; Rickards, O.; Canini, A. Grapevine carpological remains revealed the existence of a Neolithic domesticated Vitis vinifera L. specimen containing ancient DNA partially preserved in modern ecotypes. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 69, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; Inwood, J.; Clarke, S.; Crowther, A.; Covelli, D.; Favreau, J.; Itambul, M.; Steve Larter, S.; Lee, P.; Lozano, M.; et al. Structural characterization and decontamination of dental calculus for ancient starch research. Archaeol. Anthrop. Sci. 2019, 11, 4847–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. Available online: https://www.sisweb.com/software/ms/nist.htm 2017 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- FoodDB Version 1.0. Available online: http://fooddb.ca 2013 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- TGSC. The Good Scents Company. Available online: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

| Lab Code | Burial | Sex | Age at Death | Weight of Calculus (g) | Starches | Pollen Grains | Other Micro-remains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | ND | <55 | 0.040 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 4 | ND | 20–25 | 0.020 | |||

| 3 | 8 | F | 30–40 | 0.020 | 1 | 1A | |

| 4 | 9 | ND | <45 | 0.020 | 9 | ||

| 5 | 10 | ND | <45 | 0.020 | |||

| 6 | 11 | F | 20–25 | 0.090 | 3 | ||

| 7 | 12 | M | 30–35 | 0.040 | 1 | ||

| 8 | 16 | ND | 20–25 | 0.050 | |||

| 9 | 18 | ND | <30 | 0.060 | 50 | ||

| 10 | 20 | ND | 35–40 | 0.060 | 1 | 1T | |

| 11 | 21 | ND | 30–35 | 0.050 | 1T, 2F | ||

| 12 | 23 | M | 15–20 | 0.080 | |||

| 13 | 24 | M | 35–40 | 0.020 | 2 | ||

| 14 | 25 | M | 15–20 | 0.010 | |||

| 15 | 30 | M | 30–40 | 0.080 | |||

| 16 | 30 02 | IND | 4 ± 24 | 0.020 | |||

| 17 | 31 | ND | 20–25 | 0.020 | |||

| 18 | 32 | ND | <35 | 0.030 | 1 | ||

| 19 | 33 | M | 30–40 | 0.016 | |||

| 20 | 36 | F | 25–30 | 0.030 | 3 | ||

| 21 | 38 | M | 40–50 | 0.019 | 2 | ||

| Total | 69 | 5 | 3 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Agostino, A.; Canini, A.; Di Marco, G.; Nigro, L.; Spagnoli, F.; Gismondi, A. Investigating Plant Micro-Remains Embedded in Dental Calculus of the Phoenician Inhabitants of Motya (Sicily, Italy). Plants 2020, 9, 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101395

D’Agostino A, Canini A, Di Marco G, Nigro L, Spagnoli F, Gismondi A. Investigating Plant Micro-Remains Embedded in Dental Calculus of the Phoenician Inhabitants of Motya (Sicily, Italy). Plants. 2020; 9(10):1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101395

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Agostino, Alessia, Antonella Canini, Gabriele Di Marco, Lorenzo Nigro, Federica Spagnoli, and Angelo Gismondi. 2020. "Investigating Plant Micro-Remains Embedded in Dental Calculus of the Phoenician Inhabitants of Motya (Sicily, Italy)" Plants 9, no. 10: 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101395

APA StyleD’Agostino, A., Canini, A., Di Marco, G., Nigro, L., Spagnoli, F., & Gismondi, A. (2020). Investigating Plant Micro-Remains Embedded in Dental Calculus of the Phoenician Inhabitants of Motya (Sicily, Italy). Plants, 9(10), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101395