1. Introduction

Cancer is a very important cause of death globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [

1]. It corresponds to a large group of diseases, affecting different organs, with slow through to very quick progression. Although platinum complexes are the only metallodrugs approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use against cancer [

2], different metal complexes have been developed as alternatives, trying to bypass induced resistance and severe toxic effects [

3]. Besides platinum, ruthenium, copper, gold, and vanadium compounds are being extensively investigated. Furthermore, different targets have been identified in wide-ranging studies, depending on the metal and on the ligand.

A primary target in such studies is DNA, and different metal complexes exhibit quite different binding constants, depending on the nature of the metal ion and the structural features of the ligands. Usually, three types of interactions can occur: intercalation, covalent bonds, and electrostatic interactions [

4]. For complexes of redox active metal ions, such as iron or copper, oxidative stress plays an important rule, usually causing single and double strand scission by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and can lead to a wide array of DNA lesions implicated in the etiology of many human diseases [

5]. Many metal complexes reported as anticancer agents act by an oxidative mechanism involving ROS, in a process modulated by the ligand that is responsible for changes in charge, redox potential, and geometry around the metal, affecting different organelles [

6].

However, although most of the reported studies focus on DNA, considerable efforts have been made in unravelling mechanistic details of new metal-based drugs [

7], including speciation of the most active compounds, identification of critical regulatory genes, and search for alternative targets. An array of different strategies are being developed to circumvent cancer hallmarks [

8]. Most of the potential metallodrugs investigated are multifunctional, interacting with diverse biomolecules. As alternative targets, kinases [

9], topoisomerases [

10], and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [

11] have received high interest in the literature, since these proteins play crucial roles in cell-cycle progression and differentiation, and several types of cancer are associated with deregulation in these activities.

Among the new developed anticancer metal complexes, copper has a deserved special interest, coordinated to a wide range of ligands [

12], some of them acting as intercalators to DNA [

13] or groove binders [

14]. In this scenario, Schiff base complexes have allowed important progress in the field. Classical diimines or Schiff bases, such as phenanthroline and correlated planar ligands, are common examples of DNA intercalators, acting efficiently as artificial metallonucleases [

15]. Since many copper compounds show preference for interaction with guanine moieties [

16], investigations into new complexes able to act as G-quadruplex DNA binders have increased significantly [

17]. Further, there is evidence that G-quadruplex structures are improved in cancer cells compared to healthy ones [

18]. Therefore, different metal complexes have been reported interacting with both duplex and quadruplex DNA, especially with Schiff base ligands [

19]. Recently, two dinuclear copper(II) complexes based on phenanthroline ligands were shown to promote oxidative damage to DNA and mitochondria through the formation of singlet oxygen and superoxide radicals, causing double strand breaks and mitochondrial membrane depolarization [

20]. Furthermore, these compounds are able to discriminate oligomer sequences, mediating Z-like DNA formation.

Isatin (1

H-indole-2,3-dione, or 2,3-dioxoindoline), an endogenous oxindole widely distributed in different tissues in mammals, is formed in the metabolism of amino acids such as tryptophan, and some of its derivatives have demonstrated a wide range of effects in biological media, including inhibition of monoamine oxidase, anti-viral, fungicidal, bactericidal, and anti-proliferative activities [

21]. Schiff base ligands containing an oxindole group also exhibited pharmacological properties, especially anti-convulsing, anti-depressive, analgesic, and anti-inflamatory activities [

22], and these properties were improved when coordinated to metal ions [

23]. Further, synthetic isatin derivatives were developed as potent kinase inhibitors, exhibiting good antineoplastic and anti-angiogenesis activities [

24,

25], and some of them entered into clinical tests [

26], being approved by FDA, such as, for instance, sunitinib malate (SU11248; Sutent

®; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA).

With the aim of preparing new metal complexes that exhibit promising pharmacological or medicinal activity in neoplastic processes, we have designed and isolated some oxindolimines and their corresponding metal complexes, inspired by such oxindole derivatives [

27,

28]. Therefore, we have investigated a series of oxindolimine–metal complexes as pro-apoptotic compounds toward different tumor cells, trying to elucidate their possible modes of action and verifying their potential as alternative antitumor agents.

As delocalized lipophilic cations [

29,

30], they are able to enter the cell and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing oxidative damage and triggering AMPK-dependent apoptosis in different tumor cells. DNA and mitochondria were reported as their main targets. In more recent studies, a significant inhibition of crucial proteins, kinase (CDK1/cyclin B) [

31] and topoisomerase IB [

32], was additionally verified, emphasizing the contribution of the ligand to the reactivity of such complexes, and their behavior as multifunctional compounds. Interactions of the ligands at the active cavity of the proteins, mostly through hydrogen bonds and stacking, modulate the activity of such complexes [

31,

32]. These compounds exhibited high thermodynamic stability when tested using human serum albumin (has) as a competitive biological ligand. The relative stability constants determined for this series of compounds are very similar to those of copper ions inserted at the N-terminal of the protein (pK = 12) or of zinc ions bound at Cys34 residue (pK = 7) [

31].

Herein, a copper(II) and an analogous zinc(II) complex of a new oxindolimine ligand, derived from isatin and 2-aminomethylbenzimidazole and designed to facilitate intercalative interactions, were investigated for their oxidative ability and cytotoxicity toward human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and neuroblastomas (SH-SY5Y), trying to improve their antiproliferative properties in relation to previously studied related compounds.

2. Results and Discussion

The new complexes, named here [Cu(isambz)

2]

2+ 1 and [Zn(isambz)]

2+ 2, (see

Figure 1) were prepared according to a similar procedure used in a series of other oxindolimine–metal compounds previously studied [

27,

28]. After characterization by UV/Vis and IR spectroscopies (see Experimental Section), their reactivity versus human serum albumin (HSA) and CT-DNA was investigated.

The copper(II) complex was isolated as 1:2 species, with ligands in the keto form, while the analogous zinc(II) was obtained as the 1:1 species, with the ligands in the enol form. Both species can be obtained by controlling the pH of the solution during the syntheses. However, in solution there is an equilibrium (

Scheme 1) between those two forms depending on the pH, involving tautomeric forms of the ligands, similarly to what was observed in correlated complexes [

28].

In further experiments, the analogous copper(II) compound [Cu(isambz)]ClO

4 was isolated and the EPR spectra of both copper(II) species were compared in order to clarify their structural features. Based on the spectroscopic parameters determined, the compound 1:2 showed a more tetrahedral distorted structure (g

///A

// = 182 cm), while the complex 1:1 exhibited a tetragonal configuration (g

///A

// = 116 cm), according to a semi-empirical approach [

33].

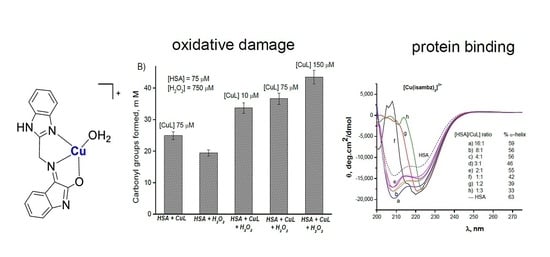

Initially, the ability of the copper complex 1 in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) was tested after 10 min incubation of this complex with hydrogen peroxide, by EPR measurements, using the spin trapping method. In

Figure 2, it can be seen that up to 150 μM this complex is not very oxidative, forming a limited amount of hydroxyl radicals, as detected by DMPO–OH adducts. However, in complementary experiments at much lower concentrations, it was able to oxidize HSA, as monitored by carbonyl groups formation through reaction with DNPH.

By incubation of the protein with complex

1 and hydrogen peroxide, and using EPR spectroscopy, a stable protein–radical species was detected under air, at g = 1.989 (line width of 52 G), as shown in

Figure 3. A very similar species (g = 1.996, line width of 45 G) was obtaining by using an analogous complex, [Cu(isaepy)

2]

2+, one of the most reactive in a series of such copper(II) complexes [

29,

30]. Studies on the oxidation of bovine serum albumin (BSA) by Cu,Zn–superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of nitrite, have identified a similar radical (g = 2.007; total line width of 54 G) [

34]. This protein-bound radical is very stable, detectable at room temperature and under air, and was identified as a protein–Tyr· species. It was also reported in the heme detoxification process by HSA, inhibiting further destructive or irreversible oxidation of the protein [

35].

Further studies by CD spectroscopy showed that by titrating HSA with this copper complex

1, the protein α-helix structure is substantially altered, indicating an efficient binding of the complex to the protein (see

Figure 4) that probably favors its oxidation.

However, complementary experiments by SDS PAGE (

Figure S1, supplementary material) of HSA (75 µM) incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with each of these copper(II) complexes (75 µM), in the presence or in the absence of hydrogen peroxide, did not show degradative damage (cleavage) of the protein.

2.1. Quenching of DNA–EtBr Fluorescence

Since one of the most studied targets for metal complexes is DNA, we verified by fluorescence measurements the ability of both complexes to bind to CT-DNA saturated with ethidium bromide (EtBr), a known nucleic acid intercalator.

Results in this competitive assay revealed that changes in fluorescence were more noticeable for complex

1 than for complex

2 at high concentrations of quencher [Q], as shown in

Figure 5. By using two methods, Stern–Volmer plots of

F0/

F versus [Q], and logarithmic Scathchard graphs, log(

F0 −

F)/

F versus log[Q], the corresponding binding constants

KSV as well as

Ka and binding site number

n were determined. The values of

KSV was obtained by linear fitting up to 400 µM [Q] and was higher for the copper complex

1 (4.52 × 10

2 M

−1) than for the zinc complex

2 (2.75 × 10

2 M

−1), suggesting a stacking or intercalative interaction. The difference observed can be probably attributed to a more planar structure of the copper compound relative to that of zinc, enabling an intercalation among bases.

However, for both complexes a non-collisional quenching seemed to work, as indicated by the curves obtained in Scathchard graphs (see

Figure 5). A linear plot indicates a single quenching mechanism, while a positive deviation points to different binding sites in the biomolecule available for the quenchers, usually with different affinities.

The corresponding parameters,

Ka and

n, were determined and were very low when compared to analogous values previously obtained for a series of similar Schiff base–copper(II) complexes, [Cu(isaepy)

2]

2+, [Cu(enim)H

2O]

2+, [Cu(isaenim)]

2+, and [Cu(

o-phen)

2]

2+ in competitive experiments with EtBr intercalated in plasmidial DNA (see

Table 1) [

36]. Furthermore, in the case of plasmidial DNA, the observed

Ka values are usually lower (100-fold) than for CT-DNA. For all the complexes in previous series, an efficient interaction with DNA structure was verified, with

Ka in the range of 10

2 and

n between 0.5 and 1. However, for the new complexes

1 and

2, these parameters are too low, with

Ka in the range of 10

−1 and

n between 0.2 and 0.3, indicating little binding to DNA, that is, little competitive substitution of EtBr as DNA intercalator.

The small decrease of fluorescence intensity of EB bound to CT-DNA observed upon increasing addition of the complexes

1 and

2 (up to 400 µM), shown in

Figure S2 (supplementary material), corroborates this fact. Additionally, this was reinforced by CD spectra, monitoring the decrease in the typical DNA band at 270–280 nm by increasing addition of the metal complexes, up to 250 µM (see

Figure 6). Most likely, in the case of complexes focused on herein, the main interactions occur at minor or major grooves, with slight intercalation.

2.2. Oxidative Damage to DNA

Despite not showing very significant interaction with DNA (at low concentrations), significant single and double cleavage of CT-DNA was verified in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (50 µM) and complex

1, after incubation for 30 or 60 min at 37 °C (see

Figure 7). This was the most reactive copper complex in an already investigated series of complexes regarding its nuclease activity [

37], leading to the linear DNA form III after 60 min, at 50 nM. In different experimental conditions, by using 125 mM H

2O

2, formation of linear DNA form was observed at 5 µM after 12 h incubation, as also shown in

Figure 7.

2.3. Cytotoxicity Toward Tumor Cells

The antiproliferative properties of the new complexes

1 and

2 were tested against hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG

2) and neuroblastoma cells (SHSY5Y), up to 50 µM concentration. The compounds showed different cytotoxic effects toward SHSY5Y cells which were more susceptible with respect to the HepG2 cells (

Figure 8). In particular, the zinc complex

2 did not significantly affects cell viability of HepG2 cells, but is significantly toxic for SHSY5Y cells only at 50 µM (

p < 0.01). On the contrary, copper complex

1 showed slightly toxic effect at both 25 µM and 50 µM for HepG2 cells (

p < 0.05), and a more pronounced toxicity for the SHSY5Y cells at both 25 µM and 50 µM (

p < 0.01). Therefore, the cytotoxicity of both complexes was cell type dependent. This behavior is very similar to that observed with copper(II) complexes with related ligands derived from isatin [

28,

29]. Consequently, the introduction of a more lipophilic moiety in the ligand (benzimidazole group) apparently did not significantly improve the cytotoxicity of these complexes, as expected.

In the literature [

38], [Cu(

o-phen)

2]

2+ complex has been reported to induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells by generation of ROS, with IC

50 around 5 µM after 24 h incubation at 37 °C. Its higher cytotoxicity can be explained by the almost planar arrangement of the phenanthroline rings that helps its intercalation with DNA [

39]. For both of our complexes, the main interactions with DNA probably occurred at minor or major grooves due their structure (distorted tetrahedral geometry).

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

The reagents isatin (1H-indole-2,3-dione, 98%), 2-(2-aminoethyl)pyridine (95%), 1,3-diaminopropane (98%), histamine dihydrochloride (99%), 2-aminomethylbenzimidazole dihydrochloride (99%), copper(II) perchlorate hexahydrated (98%), were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. Calf thymus DNA as sodium salt (CT-DNA) and human serum albumin (HSA) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), while most of the solvents, ethanol, methanol, and dichloromethane were from Merck Chemical Co. (Darmstadt, Germany). All the solutions were prepared with water purified in a deionizer Barnstead apparatus, model D470.

Syntheses of the Complexes

The new metal complexes with oxindolimine ligands were prepared by methodology already developed in previous studies, with suitable modifications [

27,

28]. Depending on the pH during the metalation step, tautomeric forms (keto or enol) of the ligand are preferentially formed and the corresponding metal complexes can be isolated. For complex

1, the species [CuL

2] with the ligand in the keto form was isolated at apparent pH in the range 5 to 7, while the analogous [ZnL] complex

2, with the ligand in the enol form, was isolated at pH 9. In previous studies with similar oxindolimine ligands, both complex species 1:2 (ligand in keto form) and 1:1 (ligand in enol form) could also be isolated and characterized [

36].

Complex [Cu(isambz)2](ClO4)2—complex 1: To a solution of isatin 1.47 g (10.0 mmols) dissolved in 25 mL ethanol and 25 mL CH2Cl2, 2.20g (10.0 mmols) of 2-aminomethylbenzimidazol were added, adjusting the pH to 5.5 with drops of HCl. The solution was kept under constant stirring for 24 h. Afterwards, the metallation of the formed ligand was carried out by addition of 1.85g (5.00 mmols) copper(II) perchlorate hexahydrate dissolved in 5 mL water. In this step, the pH was adjusted around 7 by adding some drops of NaOH solution, and a brown precipitate was formed. This precipitate was collected after cooling the final solution, washed with cold ethanol and ethyl ether, and finally dried in a desiccator under reduced pressure. The keto form of the ligand coordinated to the copper ion, in a 1:2 metal:ligand complex, was isolated. The yield was 74% (3.02 g). Elemental analyses: Calc. for C32H24N8O2Cu(ClO4)2 (MW= 815.05): C, 47.16; H, 2.97; N, 13.75; Experim.: C, 48.51; H, 3.05; N, 14.30. UV/Vis: λmax = 256 nm (ε = 1.61 × 10−4 M−1·cm−1), λmax = 284 nm (ε = 1.87 × 10−4 M−1·cm−1). IR (cm−1): 3343, ν(N–H); 2976, ν(Csp2–H and C=C); 1722, ν(C=O), 1614 and 1597, ν(C=N Schiff base, isatin ring and N–H); 741, ν(C–H phenyl). EPR spectra, in DMSO/water at 77K: g┴ = 2.096; g// = 2.427; A// = 118 G = 133 × 10−4 cm−1 (distorted tetrahedral symmetry). For analogous complex, isolated as 1:1 species [Cu(isambz)]ClO4, EPR spectra, in DMSO/water at 77K: g┴ = 2.107; g// = 2.450; A// = 186 G = 212 × 10−4 cm−1 (tetragonal symmetry).

Complex [Zn(isambz)Cl2]·H2O—complex 2: By a similar procedure, the analogous dark orange [Zn(isambz)Cl2] was prepared, using zinc(II) chloride instead of copper salt. In this case, a 1:1 metal:ligand complex was isolated, maintaining the pH around 9 during metalation. The yield was 58% (1.25 g). Elemental analyses: Calc. for C16H12N4OZnCl2 (MW = 430.50): C, 44.64; H, 3.28; N, 13.01; Experim.: C, 44.24; H, 3.11; N, 12.77. UV/Vis: λmax = 259 nm (ε = 8.85 × 10−3 M−1·cm−1), λmax = 284 nm (ε = 8.67 × 10−3 M−1·cm−1). IR (cm−1): 3344, ν(N–H); 2978, νCsp2–H and C=C); 1721, ν(C=O), 1613 and 1471, ν(C=N Schiff base, isatin ring and N–H); 744, ν(C–H phenyl).

3.2. Methods

Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were performed using a Perkin Elmer model 2400 analyzer (Perkin-Elmer, Billerica, MA, USA), and metal components were determined in duplicate by ICP emission spectroscopy in a Spectro Analytical Instruments equipment (Spectro/AMETEK, Kleve, Germany), at Central Analítica of our institution. UV/Vis spectra were registered in a UV-1650PC spectrophotometer from Shimadzu (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan), using 1.00 cm optical length quartz cells. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of samples were recorded in the 4000–400 cm−1 range on a Bruker FTIR ALPHA (Bruker, Billerica, USA) equipped with a single reflection diamond ATR module with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. EPR experiments were conducted in a Bruker EMX spectrometer operating at X-band (standard conditions: frequency 9.51 GHz, microwave power 20.12 mW, modulation frequency 100 kHz) (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany), using Wilmad flat cells. HSA-radical was registered directly, at room temperature, after incubation of the protein with complex 1 or [Cu(isaepy)] (100 µM), and immediately after addition of hydrogen peroxide (2.5 mM). 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, 100 mM) and 4-hydroxy-1-oxyl-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (Tempol, 36 µM) were used as spin trap and calibrant respectively, in spin trapping EPR experiments, to detect hydroxyl radical generation in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and complex 1.

3.2.1. Interactions with Biomolecules Monitored by CD Spectroscopy

Interactions of complex

1 with HSA were monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, in the range 190 to 300 nm, in a JASCO J-720 spectropolarimeter. The spectra (double scan) were registered in a spherical quartz cell (0.10 cm optical path), after increasing addition of complex

1 (stock solution 1.0 mM) to HSA solution (2.5 µM), in phosphate buffer 50 mM containing 0.10 M NaCl, at pH 7.4 at room temperature. Results were expressed as residual elipsicity (θ), defined as θ (deg cm

2/dmol) = CD (mdeg)/10 ×

n ×

l ×

Cp, where CD is the measure in mdeg,

n is the number of amino acid residues (for HSA,

n = 585),

l is the optical path, and

Cp is the protein concentration [

40].

Binding to DNA was monitored through a typical DNA band at 270–280 nm, using the same instrument, a JASCO J-720 spectropolarimeter (JASCO Inc., Easton, MD, USA). Decreasing intensity of this band (DNA 50 µM) was verified by addition of increasing concentrations of complex 1 or 2, up to 250 µM.

3.2.2. Monitoring HSA Damage

Oxidation of the protein was detected by following the formation of carbonyl groups through reaction with dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) [

41], after incubation of HSA with the copper complex

1 for 30 min at 37 °C, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.

Samples of HSA (75 µM) were incubated with hydrogen peroxide (750 µM) and different concentrations of copper complex

1 at 37 °C for 30 min. To each sample was added 1 mL of 0.10 M DNPH solution in HCl 1 M, and the mixture was incubated for more 30 min at the same temperature. After cooling, 1.5 mL of 1 M NaOH solution was added, and the formation of corresponding dinitrophenylhydrazones was monitored spectrophotometrically, at 370 nm (ε = 22,000 M

−1·cm

−1) [

42].

3.2.3. Fluorescence Measurements with DNA and Ethidium Bromide

The fluorescence assays were performed by using fixed concentrations of CT-DNA (30 µM) and ethidium bromide (EtBr, 50 µM), and adding varying concentration of each metal complex as a quencher (20–3000 µM). The CT-DNA concentration per nucleotide was determined by absorption spectrometry with a molar extinction coefficient value of 6600 M−1·cm−1 at 260 nm. A SPEX-Fluorolog 2 spectrometer (Horiba Scientific, Kyoto, Japan) was used in fluorescence intensity measurements, with excitation wavelength at 510 nm and emission wavelength in the range of 530–800 nm. All these measurements were made by taking fresh solution each time in a quartz cell with 1.00 cm optical path, and the acquisitions were performed at 37 °C under lower and constant stirring. The maximum fluorescence resembles at 587 nm, and the first acquisition for each set of data was made in the absence of the quencher (complex). The initial fluorescence intensity was called F0, and the subsequent fluorescence intensities at a fixed solution concentration were entitled as F.

To describe the fluorescence quenching of the EtBr in a competitive reaction between CT-DNA and the complexes [Cu(isambz)

2]

2+ 1 and [Zn(isambz)]

2+ 2, two different mathematical methods were used. The first method describes a dynamic process in which the quenching mechanism is mainly due to collision and can be described by the linear Stern–Volmer equation [

43],

F0/

F = 1 +

Kqτ

0[Q] = 1 +

KSV[Q], where

F0 and

F represent the fluorescence intensities in the absence and in the presence of different quencher concentration [Q] in mole per liter, respectively. The product

Kqτ

0 is known as the Stern–Volmer constant,

KSV, and it is a parameter that responds to the availability of the quencher to the fluorophore. The fluorophore quenching rate constant is given by

Kq,

KSV is the quenching constant, and τ

0 is the lifetime of the fluorophore in the absence of a quencher. When non linearity occurs in the experimental data, the quenching mechanism is not purely collisional. This variation may be due either to the ground state complex formation or to the static quenching model [

44]. The second method, described using the expression log[(

F0 −

F)/

F] = log

KA +

n log[Q], expresses the binding constant and the number of binding sites per nucleotide (

n) for the new species formed between the studied compound and the CT-DNA. The linear correlation log[(

F0 −

F)/

F] versus log[Q] gives an equation where the slope corresponds to the binding stoichiometry (

n), and the intercept gives the

Ka (10

intecept=

Ka). In our experiments, fitting was restricted up to 400 µM quencher concentration.

3.2.4. DNA Cleavage Studies

In these experiments, the plasmid pBluescript II (Stratagene, San Diego, USA) was used after purification, using Qiagen plasmid purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Mixtures of 240 ng of supercoiled DNA (Form I), in 20 µL total volume containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), in the presence or absence of hydrogen peroxide and varying concentrations of complex 1 were incubated at 37 °C for different periods of time. Stock solutions of the complexes (1.0 mM) were prepared by dissolving them in small amounts of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, 0.5 to 1 mL), and immediately diluting appropriate samples to the desired concentration with buffer solution. The final amount of DMSO was ≤1%. After incubation, a quench buffer solution (4 µL) was added, and the final solution was subjected to electrophoresis on an 1% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris–acetate, 1 mM EDTA) at 100 V, for 2 h.

3.2.5. Cytotoxicity Assays In Vitro

Human hepatoma cells, HepG2, and neuroblastoma cells, SHSY5Y, were purchased from the European Cell Culture Collection and grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s/F12 medium supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, respectively, at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air.

Cells were routinely trypsinized and plated at 30 × 105/75 cm2 flasks until sub-confluence. For the experiments, cells were plated on multiwell at 2 × 105 cells/ml and treated after 24 h. The complexes were dissolved in DMSO (stock solution 1.0 mM), and used at different concentrations (1 µM, 10 µM, 25 µM, and 50 µM). Cytotoxicity assay was performed at 24 h. Cells were collected in the medium by a scraper and harvested by centrifugation at 1000 rpm × 5 min. Cell pellets were washed once in phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.4. Cell viability was estimated by direct count with a Toma’s chamber upon Trypan blue exclusion.

4. Conclusions

Two novel complexes were obtained with an oxindolimine ligand, and had their oxidative properties toward HSA and DNA verified. Their cytotoxicities against tumor cells (HepG2 and SHSY5Y) were verified to be only moderate, in comparison to similar copper(II) complexes in the literature, and were then correlated with these oxidative properties, to clarify the main targets or modes of action of these studied complexes. This type of ligand exhibits tautomers in solution, depending on the pH, leading to corresponding keto and enol forms of copper(II) or zinc(II) complexes (

Figure 1,

Scheme 1). In the case of zinc, the 1:1 metal:ligand complex was isolated, while for copper the 1:2 species was obtained by careful control of the pH during the synthesis. According to the overall results, in both cases the 1:1 species is probably the most active toward biomolecules at pH 7.4, as already observed for other complexes in this series. However, in our studies we should consider the possibility of having both complexes 1:1 and 1:2 in equilibria, based on our previous studies with similar copper complexes, and on reported data in the literature for the speciation of different metallodrugs [

45]. In this case, the predominant species detected in solution depends primarily on the pH. The enol form of these oxindolimine ligands has a more delocalized electronic dispersion, in addition to a negative charge, since it is more easily deprotonated, and this usually leads to more stabilized and less sterically hindered metal center.

Both complexes

1 and

2 interact with HSA as well as with DNA, as detected by CD spectroscopy and fluorescence measurements, and are able to damage these biomolecules. Complex

1 is able to reasonably generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) up to 150 µM concentration, but to a remarkable extent at concentration ≥200 µM, as detected by spin trapping EPR measurements. It causes oxidative damage to has, as monitored through carbonyl group formation, and significantly affects its α-helix structure to a high extent. Additionally, a very stable protein–radical species was detected at g = 1.989 (width 52G) by EPR spectroscopy after treatment with complex

1 in the presence of H

2O

2 at room temperature. This radical was attributed to a protein-bound radical, HAS–Tyr· species, by comparison to a similar one, already identified in the literature, by treatment of bovine serum albumin (BSA) with Cu,Zn–superoxide dismutase, and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of nitrite [

40]. Furthermore, this radical has been implicated in heme detoxification process by HSA, and seems to protect the protein against other potentially more toxic effects of this oxidant [

41]. Therefore, the formation of such intermediary species attested to the remarkable oxidative properties of both copper(II) complexes investigated, complex

1 and [Cu(isaepy)

2]

2+. Interactions with HSA and other extracellular proteins can collaborate to decrease the amount of complexes entering the cells, and therefore contribute to their lower observed cytotoxicity.

The copper complex

1 is also capable of oxidizing DNA at very low IC

50, in nM concentration range, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (50 µM). It leads to single and double strand cleavage after 60 min incubation at 37 °C, despite not binding remarkably to DNA by intercalation, as attested by fluorescence quenching in competitive measurements with EtBr. Compared to other copper complexes with analogous ligands, this new copper compound showed much better oxidative properties, although it exhibited only moderate anti-proliferative effect against hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG

2) and neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y) tumor cells [

29]. Additionally, the analogous zinc complex

2, with no redox properties, exhibited similar cytotoxic effects against the same tumor cells. The ligand structure can be crucial for metal activity toward DNA, as exemplified in comparative studies of copper(II) complexes with correlated ligands, 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy), 2,2′-dipyridylamine (dpa) or dipicolylamine (dpca), where [Cu(bpy)

2]

2+ complex was the most active in double cleavage reaction [

46].

These data can also be indicative of alternative targets inside the cell in addition to DNA, in a process modulated by the metal ion, by the ligand, as well as by the predominant metal–ligand species formed. This class of metal complexes has already shown good inhibition activity toward kinases [

31] and topoisomerases [

32], and the remarkable ability to damage mitochondria [

30].

These results point to other factors than oxidative assets in determining the reactivity of these compounds. A more voluminous and sterically hindered ligand can be responsible for the verified decreased toxicity of complexes

1 and

2, due to difficulties in entering the cell or intercalating at DNA structure. Their low solubility in aqueous solution is also a factor to consider. More recent studies in the development of metallodrugs use the strategy of inserting the active compounds into nanostructured materials, trying to increase their stability and efficiency in achieving their biological targets, as well enhancing anticancer activity. [Cu(phen)]Cl

2 complex, an inhibitor of aquaporin, was successfully incorporated into different liposomes, preserving its cytotoxicity against different tumor cells [

47]. These copper loaded liposomes seem to have therapeutic potential for the treatment of solid tumors, based on their preferential accumulation. In other investigations, two correlated oxindolimine complexes based on copper and zinc, for which the anticancer properties had been already verified [

29] were immobilized in functionalized nanoporous silica, and the obtained materials exhibited increased antiproliferative activity against melanomas [

48]. They were monitored inside the cells, and released the active compounds in a kinetic process that depended on the metal. For the copper based materials, a 98% release was observed after 24 h at 37 °C, while for the analogous zinc based materials an 80% or 55% release could be verified, depending on the matrix used.

Our results confirmed DNA as an important target for these oxindolimine–metal complexes, as already observed [

29], and additionally pointed out that oxidative damage is not the leading mechanism responsible for the cytotoxicity of this class of compounds.