Endothelial Dysfunction and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Versus Established Diabetes: From the CORDIOPREV Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

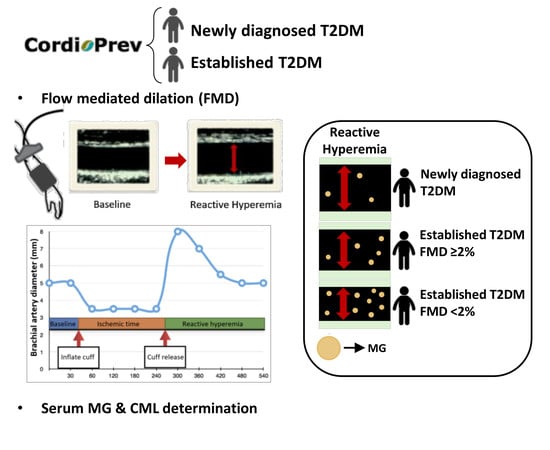

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements and Laboratory Tests

2.3. Evaluation of Endothelial Function

2.4. Estimation of Severity of Endothelial Dysfunction

2.5. Ultrasound Measurement of IMT-CC

2.6. Determination of Serum Levels of AGEs

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low Wang Cecilia, C.; Hess Connie, N.; Hiatt William, R.; Goldfine Allison, B. Clinical Update: Cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2016, 133, 2459–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcox, J.P.J.; Schenke, W.H.; Zalos, G.; Mincemoyer, R.; Prasad, A.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Nour, K.R.A.; Quyyumi, A.A. Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2002, 106, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoluci, M.C.; Cé, G.V.; da Silva, A.M.; Wainstein, M.V.; Boff, W.; Puñales, M. Endothelial dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celermajer, D.S.; Sorensen, K.E.; Gooch, V.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Miller, O.I.; Sullivan, I.D.; Lloyd, J.K.; Deanfield, J.E. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 1992, 340, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touboul, P.; Hennerici, M.; Meairs, S.; Adams, H.; Amarenco, P.; Bornstein, N.; Csiba, L.; Desvarieux, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Hernandez, R.H.; et al. Mannheim Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Plaque Consensus (2004–2006–2011): An Update on Behalf of the Advisory Board of the 3rd and 4th Watching the Risk Symposium 13th and 15th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, and Brussels, Belgium, 2006. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 34, 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- Fournet, M.; Bonté, F.; Desmoulière, A. Glycation damage: A possible hub for major pathophysiological disorders and aging. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stirban, A.; Gawlowski, T.; Roden, M. Vascular effects of advanced glycation endproducts: Clinical effects and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.-Y.; Cooper, M.E. The role of advanced glycation end products in progression and complications of diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kold-Christensen, R.; Johannsen, M. Methylglyoxal metabolism and aging-related disease: Moving from correlation toward causation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, S.R.; Baynes, J.W. CML: A brief history. Int. Congr. Ser. 2002, 1245, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; Nicklett, E.J.; Ferrucci, L. Does accumulation of advanced glycation end products contribute to the aging phenotype? J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2010, 65, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aso, Y.; Inukai, T.; Tayama, K.; Takemura, Y. Serum concentrations of advanced glycation endproducts are associated with the development of atherosclerosis as well as diabetic microangiopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2000, 37, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajikawa, M.; Nakashima, A.; Fujimura, N.; Maruhashi, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Iwamoto, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Oda, N.; Hidaka, T.; Kihara, Y.; et al. Ratio of serum levels of AGEs to soluble form of RAGE is a predictor of endothelial function. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalousová, M.; Skrha, J.; Zima, T. Advanced glycation end-products and advanced oxidation protein products in patients with diabetes mellitus. Physiol. Res. 2002, 51, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Kilhovd, B.K.; Berg, T.J.; Birkeland, K.I.; Thorsby, P.; Hanssen, K.F. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro-Paavonen, A.; Zhang, W.-Z.; Venardos, K.; Coughlan, M.T.; Harris, E.; Tong, D.C.K.; Brasacchio, D.; Paavonen, K.; Chin-Dusting, J.; Cooper, M.E.; et al. Advanced glycation end-products induce vascular dysfunction via resistance to nitric oxide and suppression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.B.; Chow, W.-S.; Ai, V.H.G.; Metz, C.; Bucala, R.; Lam, K.S.L. Advanced glycation end products and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ninomiya, H.; Katakami, N.; Sato, I.; Osawa, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Takahara, M.; Kawamori, D.; Matsuoka, T.; Shimomura, I. Association between subclinical atherosclerosis markers and the level of accumulated advanced glycation end-products in the skin of patients with diabetes. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2018, 25, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, X.; Ren, L.; Wei, Q.; Shao, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, N. Advanced glycation end-products decreases expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase through oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgado-Lista, J.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Garcia-Rios, A.; Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Perez-Caballero, A.I.; Gomez-Delgado, F.; Fuentes, F.; Quintana-Navarro, G.; Lopez-Segura, F.; Ortiz-Morales, A.M.; et al. Coronary Diet Intervention with Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention Study (The Cordioprev Study): Rationale, Methods, and Baseline Characteristics. Am. Heart J. 2016, 177, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ADA 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, S13–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Tinker, L.; Howard, B.V.; Kuller, L.H.; Nathan, L.; Rifai, N.; Liu, S. Insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion determined by homeostasis model assessment and risk of diabetes in a multiethnic cohort of women: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corretti, M.C.; Anderson, T.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Celermajer, D.; Charbonneau, F.; Creager, M.A.; Deanfield, J.; Drexler, H.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Herrington, D.; et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: A report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fathi, R.; Haluska, B.; Isbel, N.; Short, L.; Marwick, T.H. The relative importance of vascular structure and function in predicting cardiovascular events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, J.H.; Korcarz, C.E.; Hurst, R.T.; Lonn, E.; Kendall, C.B.; Mohler, E.R.; Najjar, S.S.; Rembold, C.M.; Post, W.S.; American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: A consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, L.E.; Lee, R.T.; Rivero, J.; Jamacochian, M.; Arroyo, L.H.; Briggs, W.; Rifai, N.; Libby, P.; Creager, M.A.; Ridker, P.M. Circulating cell adhesion molecules are correlated with ultrasound-based assessment of carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 1765–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vlassara, H.; Uribarri, J. Advanced glycation end products (AGE) and diabetes: Cause, effect, or both? Curr. Diab. Rep. 2014, 14, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamagishi, S.; Ueda, S.; Okuda, S. Food-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs): A novel therapeutic target for various disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2832–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, A.; Howell, S.; Schwenke, D.C.; Bahn, G.; Beisswenger, P.J.; Reaven, P.D. Advanced glycation end products, oxidation products, and the extent of atherosclerosis during the VA Diabetes Trial and Follow-up Study. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Sandu, O.; Peppa, M.; Goldberg, T.; Vlassara, H. Diet-derived advanced glycation end products are major contributors to the body’s AGE pool and induce inflammation in healthy subjects. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1043, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 911–916.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uribarri, J.; Stirban, A.; Sander, D.; Cai, W.; Negrean, M.; Buenting, C.E.; Koschinsky, T.; Vlassara, H. Single oral challenge by advanced glycation end products acutely impairs endothelial function in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2579–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tan, K.C.B.; Shiu, S.W.M.; Wong, Y.; Tam, X. Serum advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are associated with insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Ramdas, M.; Goodman, S.; Pyzik, R.; Chen, X.; Zhu, L.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Restriction of advanced glycation end products improves insulin resistance in human type 2 diabetes: Potential role of AGER1 and SIRT1. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Moreno, J.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Camargo, A.; Jiménez-Lucena, R.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Marín, C.; Tinahones, F.J.; Striker, G.E.; Roche, H.M.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; et al. Dietary fat quantity and quality modifies advanced glycation end products metabolism in patients with metabolic syndrome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1601029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, J.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Delgado-Lista, J.; García-Ríos, A.; Delgado-Casado, N.; Camargo, A.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; Striker, G.E.; Tinahones, F.J.; Pérez-Jiménez, F.; et al. Mediterranean Diet reduces serum advanced glycation end products and increases antioxidant defenses in elderly adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes (n = 190) | Patients with Established Diabetes (n = 350) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.0 ± 0.6 | 61.9 ± 0.4 | 0.015 |

| Sex (men/women) | 158/32 | 285/64 | 0.724 |

| Weight (kg) | 86.7 ± 1.0 | 85.0 ± 0.8 | 0.191 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.4 ± 0.3 | 31.1 ± 0.3 | 0.431 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 106 ± 0.8 | 105 ± 0.6 | 0.294 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.9 ± 0.9 | 76.1 ± 0.6 | 0.448 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 137 ± 1.5 | 143 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 41.5 ± 0.7 | 39.6 ± 0.5 | 0.023 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 92.4 ± 1.9 | 82.5 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 146 ± 6.0 | 150 ± 4.1 | 0.604 |

| ApoA-1 (mg/dL) | 127± 1.4 | 125 ± 1.2 | 0.294 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 77.3 ± 1.4 | 72.4 ± 1.0 | 0.005 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 120 ± 1.7 | 157 ± 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 0.024 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.27 ± 0.25 | 6.50 ± 0.43 | < 0.001 |

| HbAc1 (%) | 6.67 ± 0.06 | 7.66 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| FMD (%) | 4.11 ± 0.45 | 3.46 ± 0.35 | 0.256 |

| IMT-CC (mm) | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.025 |

| Alcohol intake (>16 g/day) (%) | 19.9 | 23.1 | 0.865 |

| Current tobacco use (%) | 12.2 | 9.8 | 0.380 |

| Antihypertensive drugs (%) | |||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers | 38.9 | 55.6 | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 16.8 | 24.9 | 0.039 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.6 | 63.6 | 0.852 |

| Nitrates | 10 | 10 | 1.000 |

| Diuretics | 42.1 | 46.7 | 0.320 |

| Lipid lowering drugs (%) | |||

| Statins | 86.8 | 85.7 | 0.795 |

| Fibrates | 0 | 2.9 | 0.017 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents (%) | 0 | 72.8 | <0.001 |

| Insulin (%) | 0 | 25.8 | <0.001 |

| Patients with Newly Diagnosed Diabetes | Patients with Established Diabetes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Endothelial Dysfunction (n = 56) | Non-Severe Endothelial Dysfunction (n = 118) | Severe Endothelial Dysfunction (n = 116) | Non-Severe Endothelial Dysfunction (n = 202) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 60.4 ± 1.2 | 59.8 ± 0.8 | 62.3 ± 0.7 | 61.4 ± 0.6 | 0.112 |

| Sex (men/women) | 46/10 ab | 98/20 ab | 87/29 b | 175/27 a | 0.074 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.7 ± 1.5 | 88.1 ± 1.3 | 84.6 ± 1.4 | 85.2 ± 1.1 | 0.229 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.5 ± 0.5 | 31.6 ± 0.4 | 31.2 ± 0.4 | 31.2 ± 0.4 | 0.877 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 104 ± 1.3 | 107 ± 1.1 | 104 ± 1.1 | 105 ± 0.8 | 0.204 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.6 ± 1.6 | 76.7 ± 1.0 | 74.2 ± 0.9 | 77.4 ± 0.7 | 0.062 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 141 ± 2.7 ab | 136 ± 1.8 a | 145 ± 2.0 b | 143 ± 1.4 b | 0.018 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 41.0 ± 1.4 | 41.6 ± 0.8 | 40.0 ± 1.0 | 39.1 ± 0.6 | 0.128 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 93.5 ± 3.8 a | 92.6 ± 2.5 a | 85.8 ±2.7 ab | 81.7 ± 1.7 b | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 151 ± 12.2 | 142 ± 7.0 | 161 ± 7.2 | 146 ± 5.4 | 0.253 |

| ApoA-1 (mg/dL) | 125 ± 2.6 | 128 ± 1.7 | 127 ± 2.2 | 124 ± 1.4 | 0.221 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 81.5 ± 3.0 a | 75.8 ± 1.8 ab | 74.9 ± 1.8 ab | 71.8 ± 1.3 b | 0.007 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 122 ± 3.4 a | 118 ± 2.1 a | 155 ± 6.0 b | 155 ± 3.4 b | <0.001 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 11.2 ± 1.0 ab | 10.4 ± 0.7 b | 15.2 ± 1.7 a | 12.9 ± 1.0 ab | 0.052 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.27 ± 0.52 ab | 4.18 ± 0.31 b | 7.06 ± 0.9 a | 6.09 ± 0.45 ab | 0.002 |

| HbAc1 (%) | 6.81 ± 0.11 a | 6.63 ± 0.08 a | 7.57 ± 0.13 b | 7.72 ± 0.09 b | <0.001 |

| FMD (%) | −1.78 ± 0.70 a | 6.91 ± 0.34 b | −2.19 ± 0.45 a | 6.70 ± 0.30 b | <0.001 |

| IMT-CC (mm) | 0.74 ± 0.02 ab | 0.72 ± 0.01 a | 0.76 ± 0.02 b | 0.75 ± 0.01 ab | 0.162 |

| Alcohol intake (>16 g/day) (%) | 21.8 | 19.1 | 22.4 | 23.1 | 0.682 |

| Current tobacco use (%) | 17.9 a | 7.8 b | 9.9 ab | 8.7 ab | 0.176 |

| Antihypertensive drugs (%) | |||||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers | 28.6 a | 43.2 ab | 61.2 c | 51.5 b,c | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 12.5 | 19.5 | 21.6 | 24.8 | 0.236 |

| Beta-blockers | 62.5 | 62.7 | 65.5 | 62.4 | 0.950 |

| Nitrates | 8.9 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 11.4 | 0.442 |

| Diuretics | 41.1 abc | 40.7 c | 55.2 b | 43.1 ac | 0.094 |

| Lipid lowering drugs (%) | |||||

| Statins | 87.5 | 84.7 | 83.6 | 87.1 | 0.805 |

| Fibrates | 0 ab | 0 b | 3.4 a | 3.0 ab | 0.129 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents (%) | 0 a | 0 a | 73.3 b | 72.8 b | <0.001 |

| Insulin (%) | 0 a | 0 a | 26.7 b | 24.8 b | <0.001 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Cruz-Ares, S.; P. Cardelo, M.; M. Gutiérrez-Mariscal, F.; D. Torres-Peña, J.; García-Rios, A.; Katsiki, N.; M. Malagón, M.; López-Miranda, J.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; M. Yubero-Serrano, E. Endothelial Dysfunction and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Versus Established Diabetes: From the CORDIOPREV Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010238

de la Cruz-Ares S, P. Cardelo M, M. Gutiérrez-Mariscal F, D. Torres-Peña J, García-Rios A, Katsiki N, M. Malagón M, López-Miranda J, Pérez-Martínez P, M. Yubero-Serrano E. Endothelial Dysfunction and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Versus Established Diabetes: From the CORDIOPREV Study. Nutrients. 2020; 12(1):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010238

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Cruz-Ares, Silvia, Magdalena P. Cardelo, Francisco M. Gutiérrez-Mariscal, José D. Torres-Peña, Antonio García-Rios, Niki Katsiki, María M. Malagón, José López-Miranda, Pablo Pérez-Martínez, and Elena M. Yubero-Serrano. 2020. "Endothelial Dysfunction and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Versus Established Diabetes: From the CORDIOPREV Study" Nutrients 12, no. 1: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010238

APA Stylede la Cruz-Ares, S., P. Cardelo, M., M. Gutiérrez-Mariscal, F., D. Torres-Peña, J., García-Rios, A., Katsiki, N., M. Malagón, M., López-Miranda, J., Pérez-Martínez, P., & M. Yubero-Serrano, E. (2020). Endothelial Dysfunction and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Versus Established Diabetes: From the CORDIOPREV Study. Nutrients, 12(1), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010238