Pentacoordinated Chloro-Iron(III) Complexes with Unsymmetrically Substituted N2O2 Quadridentate Schiff-Base Ligands: Syntheses, Structures, Magnetic and Redox Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Syntheses

2.2. FT-IR Spectroscopy

N), ν(C

N), ν(C  O) and ν(C

O) and ν(C  C) stretching modes of the Schiff-base skeleton. Likewise, two strong bands in the 1480–1340 cm−1 range have been assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric vibrational modes of the –NO2 group [35,36]. The solid-state FT-IR spectra of the complexes 3 and 5 show a quite similar absorption band pattern (see Section 3.2), suggesting the analogy of their molecular structures. The disappearance of both the ν(O–H) and ν(N–H) absorption bands in the spectrum of complex 3 and the bathochromic shift by 8 cm−1 of the ν(C

C) stretching modes of the Schiff-base skeleton. Likewise, two strong bands in the 1480–1340 cm−1 range have been assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric vibrational modes of the –NO2 group [35,36]. The solid-state FT-IR spectra of the complexes 3 and 5 show a quite similar absorption band pattern (see Section 3.2), suggesting the analogy of their molecular structures. The disappearance of both the ν(O–H) and ν(N–H) absorption bands in the spectrum of complex 3 and the bathochromic shift by 8 cm−1 of the ν(C  N) stretching of the azomethine group upon complex formation [37,38] indicate that the acyclic [N2O2]2− ligand is bonded to the iron(III) ion in its dianionic form and in a tetradentate fashion through the N2O2-donor set of the Schiff-base ligand.

N) stretching of the azomethine group upon complex formation [37,38] indicate that the acyclic [N2O2]2− ligand is bonded to the iron(III) ion in its dianionic form and in a tetradentate fashion through the N2O2-donor set of the Schiff-base ligand.2.3. NMR Spectroscopy

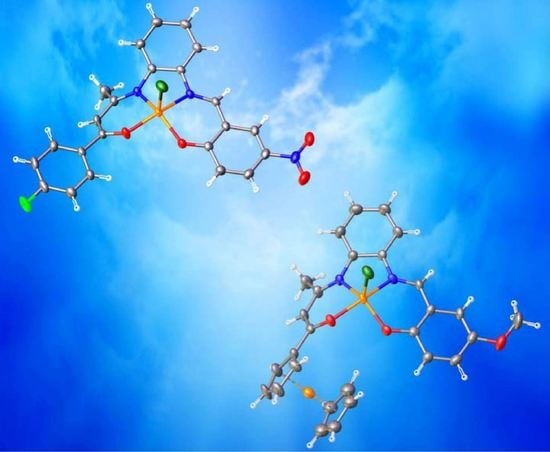

2.4. Crystal Structures

2.5. Electronic Absorption Spectra

2.6. Electrochemical Properties

2.7. Magnetic Measurements

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. X-ray Crystal Structure Determination Measurements

3.2. Synthetic Procedures

3.2.1. [(4-F–C6H4)C(O)CH=C(CH3)N(H)-o-C6H4N=CH–(2-OH,5-NO2–C6H3)] (2)

N), ν( C

N), ν( C  O) and/or ν(C

O) and/or ν(C  C), 1479(s), 1338(s) νasym(NO2), νsym(NO2), 1296(s) ν(C–F). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): 13.71 (s, 1 H, O–H), 13.05 (br s, 1 H, N–H), 8.79 (s, 1 H, N=CH), 8.41 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, o-C6H4), 8.20 (dd, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, C6H3), 7.92 (dd, 2 H, J =8.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, p-C6H4), 7.37 (m, 4 H, o-C6H4 + C6H3), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 1 H, o-C6H4), 7.11 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, C6H4F), 7.02 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H, o-C6H4), 5.94 (s, 1 H, CH=C), 2.09 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD2Cl2): 187.8 (C=O), 166.9 (C–OH), 165.1 (d, JC,F = 252 Hz, C–F), 162.9 (CH=C), 162.4 (N=CH), 143.0 (C–NO2), 140.6 (C–N=), 136.6 (C–NH), 133.9 (Cquat, C6H4F), 129.7 (d, JC,F = 9 Hz, CH, C6H4F), 129.0 (CH, o-C6H4), 128.8 (CH, o-C6H4), 128.7 (CH, o-C6H4), 127.8 (CH, C6H3), 127.3 (CH, C6H3), 119.4 (CH, C6H3), 119.0 (Cquat, C6H3–CH=N), 118.6 (CH, o-C6H4),115.4 (d, JC,F = 21 Hz, CH, C6H4F), 94.6 (CH=C), 20.5 (CH3). 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD2Cl2): −110.15 (s, CF).

C), 1479(s), 1338(s) νasym(NO2), νsym(NO2), 1296(s) ν(C–F). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): 13.71 (s, 1 H, O–H), 13.05 (br s, 1 H, N–H), 8.79 (s, 1 H, N=CH), 8.41 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz, o-C6H4), 8.20 (dd, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, C6H3), 7.92 (dd, 2 H, J =8.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, p-C6H4), 7.37 (m, 4 H, o-C6H4 + C6H3), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 1 H, o-C6H4), 7.11 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, C6H4F), 7.02 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1 H, o-C6H4), 5.94 (s, 1 H, CH=C), 2.09 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD2Cl2): 187.8 (C=O), 166.9 (C–OH), 165.1 (d, JC,F = 252 Hz, C–F), 162.9 (CH=C), 162.4 (N=CH), 143.0 (C–NO2), 140.6 (C–N=), 136.6 (C–NH), 133.9 (Cquat, C6H4F), 129.7 (d, JC,F = 9 Hz, CH, C6H4F), 129.0 (CH, o-C6H4), 128.8 (CH, o-C6H4), 128.7 (CH, o-C6H4), 127.8 (CH, C6H3), 127.3 (CH, C6H3), 119.4 (CH, C6H3), 119.0 (Cquat, C6H3–CH=N), 118.6 (CH, o-C6H4),115.4 (d, JC,F = 21 Hz, CH, C6H4F), 94.6 (CH=C), 20.5 (CH3). 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD2Cl2): −110.15 (s, CF).3.2.2. [{(4-F–C6H4)C(O)CH=C(CH3)N-o-C6H4N=CH–(2-O,5-NO2–C6H3)}FeCl] (3)

N), ν( C

N), ν( C  O) and/or ν(C

O) and/or ν(C  C), 1492(s) νasym (NO2), 1320(s), νsym(NO2), 1102 (m) ν(C–F).

C), 1492(s) νasym (NO2), 1320(s), νsym(NO2), 1102 (m) ν(C–F).3.2.3. [{(η5-C5H5)Fe(η5-C5H4)C(O)CH=C(CH3)N-o-C6H4N=CH–(2-O,5-OCH3–C6H3)}FeCl] (5)

N), ν(C

N), ν(C  O) and/or ν(C

O) and/or ν(C  C), 1362(vs), 1266(s), 1324(m) ν(C–O).

C), 1362(vs), 1266(s), 1324(m) ν(C–O).4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schiff, H. Mittheilungen aus dem universitätslaboratorium in pisa: Eine neue reihe organischer basen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1864, 131, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, M.D.; Smith, T.D. N,N'-ethylenebis(salicylideneiminato) transition metal ion chelates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1973, 9, 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnovskii, A.D.; Nivorozhkin, A.L.; Minkin, V.I. Ligand environment and the structure of Schiff base adducts and tetracoordinated metal-chelates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1993, 126, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigato, P.A.; Tamburini, S. Advances in acyclic compartmental ligands and related complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1871–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shi, R.; Zhou, P.; Qiu, Q.; Li, H. Asymmetric Schiff bases derived from diaminomaleonitrile and their metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1106, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, P.; Breith, E.; Lubbe, E.; Tsumaki, T. Tricyclische orthokondensierte nebenvalenzringe. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1933, 503, 84–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, J.-P.; Cros, G.; Darbieu, M.H.; Laurent, J.-P. The non-template synthesis of novel non-symmetrical, tetradentate Schiff bases. Their nickel(II) and cobalt(III) complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1982, 60, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, P.; Tarnburini, S.; Vigato, P.A. From mononuclear to polynuclear macrocyclic or macroacyclic complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1995, 139, 17–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.M.; Storr, T. The chemistry and applications of multimetallic salen complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 9380–9391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menati, S.; Amiri Rudbari, H.; Askari, B.; Riahi Farsani, M.; Jalilian, F.; Dini, G. Synthesis and characterization of insoluble cobalt(II), nickel(II), zinc(II) and palladium(II) Schiff base complexes: Heterogeneous catalysts for oxidation of sulfides with hydrogen peroxide. C. R. Chimie 2016, 19, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdzak, R.; Allaert, B.; Ledoux, N.; Dragutan, I.; Dragutan, V.; Verpoort, F. Ruthenium complexes bearing bidentate Schiff base ligands as efficient catalysts for organic and polymer syntheses. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 3055–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezenberg, S.J.; Kleij, A.W. Material Applications for Salen Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Martinez, E.; Carretero-Gonzalez, J.; Armand, M. Polymeric Schiff bases as low-voltage redox centers for sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5341–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bella, S. Second-order nonlinear optical properties of transition metal complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001, 30, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetto, S.; Di Bella, S. Synthesis, characterization, optical absorption/fluorescence spectroscopy, and second-order nonlinear optical properties of aggregate molecular architectures of unsymmetrical Schiff-base zinc(II) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 2168–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaim, W.; Schwederski, B. Bioinorganic chemistry: Inorganic elements. In The Chemistry of Life; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994; ISBN 0-471-94369-X. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, B.; Jäger, E.-G. Structure and magnetic properties of iron(II/III) complexes with N2O22− coordinating Schiff base like ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domracheva, N.; Pyataev, A.; Manapov, R.; Gruzdev, M.; Chervonova, U.; Kolker, A. Structural, magnetic and dynamic characterization of liquid crystalline iron(III) Schiff base complexes with asymmetric ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonsri, W.; Martinez, V.; Davies, C.G.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S. Ligand effects in a heteroleptic bis-tridentate iron(III) spin crossover complex showing a very high T1/2 value. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, C.; Augustín, P.; Nemec, I.; Trávnícek, Z.; Oshio, H.; Boca, R.; Renz, F. Spin crossover in iron(III) complexes with pentadentate Schiff base ligands and pseudohalido coligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 902–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, C.; Augustin, P.; Dlhan, L.; Pavlik, J.; Moncol, J.; Nemec, I.; Boca, R.; Renz, F. Iron(III) complexes with pentadentate Schiff-base ligands: Influence of crystal packing change and pseudohalido coligand variations on spincrossover. Polyhedron 2015, 87, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Kimoto, K.; Ohyoshi, A.; Maeda, Y. Synthesis and characterization of iron(III) complexes with unsymmetrical quadridentate Schiff bases, and spin equilibrium behavior in solution. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1984, 57, 3307–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, B.W.; Smith, A.W.; Larkworthy, L.F.; Rogers, K.A. Transition metal–Schiff base complexes. Part VI. Mössbauer and magnetic investigations of some iron(II) and iron(III) systems. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1973, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, H.-L.; Wei, H.-H.; Lee, G.-H.; Wang, Y. Structure, magnetic properties and epoxidation activity of iron(III) salicylaldimine complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerloch, M.; Mabbs, F.E. The crystal and molecular structure of chloro-(NN′-bis-salicylidene-ethylenediamine)iron(III) as a hexaco-ordinate Dimer. J. Chem. Soc. A 1967, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.; Thompson, M.E.; Van Engen, D. Synthesis and Nonlinear Optical Properties of Inorganic Coordination Polymers. Spec. Publ. R. Soc. Chem. 1991, 91, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Elmali, A.; Karakas, A.; Unver, H. Nonlinear optical properties of bis[(p-bromophenyl-salicylaldiminato)chloro]iron(III) and its ligand N-(4-bromo)-salicylaldimine. Chem. Phys. 2005, 309, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppasamy, P.; Thiruppathi, D.; Vijaya Sundar, J.; Rajapandian, V.; Ganesan, M.; Rajendran, T.; Rajagopal, S.; Nagarajan, N.; Rajendran, P.; Sivasubramanian, V.K. Spectral, computational, electrochemical and antibacterial studies of iron(III)-salen complexes. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2015, 40, 2945–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna, J.; Artigas, V.; Fuentealba, M.; Hamon, P.; Manzur, C.; Dorcet, V.; Hamon, J.-R.; Carrillo, D. Nickel(II) and copper(II) complexes of new unsymmetrically-substituted tetradentate Schiff base ligands: Spectral, structural, electrochemical and computational studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 462, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, A.; Barone, G.; Ruisi, G.; Lo Giudice, M.T.; Tumminello, S. The interaction of native DNA with iron(III)-N,N’-ethylene-bis(salicylideneiminato)-chloride. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2004, 98, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Darensbourg, D.J.; Ortiz, C.G.; Billodeaux, D.R. Synthesis and structural characterization of iron(III) salen complexes possessing appended anionic oxygen donor ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2004, 357, 2143–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, N.; Roisnel, T.; Hamon, P.; Kahlal, S.; Manzur, C.; Ngo, H.M.; Ledoux-Rak, I.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Carrillo, D.; Hamon, J.-R. Four-coordinate nickel(II) and copper(II) complex based ONO tridentate Schiff base ligands: Synthesis, molecular structure, electrochemical, linear and nonlinear properties, and computational study. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 18019–18037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentealba, M.; Trujillo, A.; Hamon, J.-R.; Carrillo, D.; Manzur, C. Synthesis, characterization and crystal structure of the tridentate metalloligand formed from mono-condensation of ferrocenoylacetone and 1,2-phenylenediamine. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 881, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, A.; Fuentealba, M.; Carrillo, D.; Manzur, C.; Ledoux-Rak, I.; Hamon, J.-R.; Saillard, J.-Y. Synthesis, spectral, structural, second-order nonlinear optical properties and theoretical studies On new organometallic donor-acceptor substituted nickel(II) and copper(II) unsymmetrical Schiff-base complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 2750–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celedón, S.; Fuentealba, M.; Roisnel, T.; Ledoux-Rak, I.; Hamon, J.-R.; Carrillo, D.; Manzur, C. Side-chain metallopolymers containing second-order NLO-active bimetallic NiII and PdII Schiff-base complexes: Syntheses, structures, electrochemical and computational studies. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 3012–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna, J.; Dorcet, V.; Manzur, C.; Ledoux-Rak, I.; Hamon, J.R.; Carrillo, D. Synthesis, spectral, electrochemical, crystal structures and nonlinear optical properties of unsymmetrical Ni(II) and Cu(II) Schiff base complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2015, 430, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahmoud, W.H.; Mahmoud, N.F.; Mohamed, G.G. Mixed ligand complexes of the novel nanoferrocene based Schiff base ligand (HL): Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, MOE studies and antimicrobial/anticancer activities. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 848, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouennoughi, Y.; Eddine Karce, H.; Aggoun, D.; Lanez, T.; Ruiz-Rosas, R.; Bouzerafa, B.; Ourari, A.; Morallon, E. A novel ferrocenic copper(II) complex salen-like, derived from 5-chloromethyl-2-hydroxyacetophenone and N-ferrocenmethylaniline: Design, spectral approach and solvent effect towards electrochemical behavior of Fc+/Fc redox couple. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 848, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Denisov, G.S.; Toney, M.D.; Limbach, H.-H. NMR studies of solvent-assisted proton transfer in a biologically relevant Schiff base: Toward a distinction of geometric and equilibrium H-bond isotope effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3375–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziembowska, T.; Szafran, M.; Katrusiak, A.; Rozwadowski, Z. Crystal structure of and solvent effect on tautomeric equilibrium in Schiff base derived from 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde and methylamine studied by X-ray diffraction, DFT, NMR and IR methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 929, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.D.; Orgel, L.E.; Rich, A. The crystal structure of ferrocene. Acta Crystallogr. 1956, 9, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilli, P.; Bertolasi, V.; Ferretti, V.; Gilli, G. Evidence for intramolecular N–H···O resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding in β-enaminones and related heterodienes. A combined crystal-structural, IR and NMR spectroscopic, and quantum-mechanical investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 10405–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, A.W.; Nageswara, T.; Reedijk, J.; van Rijn, J.; Verchoor, G.C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper( II) compounds containing nitrogen-sulphur donor ligands ; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerloch, M.; Mabbs, F.E. The crystal and molecular structure of NN′-bis(salicylideneiminato)-iron(III)chloride as a five-co-ordinate monomer. J. Chem. Soc. A 1967, 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmali, A.; Elerman, Y.; Svoboda, I.; Fuess, H. Structure of [N,N'-o-Phenylenebis-(salicylideneaminato)]iron(III) chloride as a five-coordinate monomer. Acta Crystallogr. 1993, C49, 1365–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elerman, Y.; Kabak, M.; Tllko, D. A Five-coordinated monomer of chloro-[N,N'-(di-2-hydroxy-1-naphthylidene)-1,2-diaminobenzene]iron(III). Acta Crystallogr. 1997, C53, 712–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmali, A.; Kavlakoglu, E.; Elerman, Y.; Svoboda, I. A complex containing both five- and six-coordinate [bis(5-bromosalicylidene)benzene-1,2-diimine]chloro-iron(III). Acta Crystallogr. 2000, C56, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaizu, K.; Tsuchida, E. Crystal structure and reactivity of a five-coordinate chloroiron(III) complex with a bulky tetradentate Schiff base ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 355, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyers, L., Jr.; Que, S.Y.; VanDerveer, D.; Bu, X.R. Synthesis and structures of new salen complexes with bulky groups. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2006, 359, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calligaris, M.; Nardin, G.; Randaccio, L. Structural aspects of metal complexes with some tetradentate schiff bases. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1972, 7, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaizu, K.; Dewi, E.L.; Tsuchida, E. A µ-oxo diiron(III) complex with a short Fe–Fe distance: Crystal structure of (μ-oxo)bis[N,N’-o-phenylenebis(salicylideneiminato)iron(III)]. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2001, 321, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, B.; Costes, J.-P.; Tommasino, J.-B.; De Montauzon, D.; Soulet, F.; Fabre, P.-L. Electrochemical studies of Iron(III) Schiff base complexes—I. The monomeric FeIII(N2O2)Cl complexes. Polyhedron 1993, 12, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armarego, W.L.F.; Chai, C.L.L. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 5th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7506-7571-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, O. Molecular Magnetism; VCH Publishers: New York, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0471188384. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bond Distances | |||

| O(1)–C(7) | 1.249(2) | O(2)–C(19) | 1.329(2) |

| N(1)–C(9) | 1.333(3) | N(2)–C(17) | 1.279(2) |

| C(7)–C(8) | 1.421(3) | C(17)–C(18) | 1.444(3) |

| C(8)–C(9) | 1.373(3) | C(18)–C(19) | 1.413(3) |

| N(1)–C(11) | 1.428(2) | N(2)–C(16) | 1.415(2) |

| F(1)–C(1) | 1.3250(17) | N(3)–C(22) | 1.460(3) |

| N(3)–O(3) | 1.220(3) | N(3)–O(4) | 1.217(3) |

| Bond Angles | |||

| O(1)–C(7)–C(8) | 122.18(19) | O(2)–C(19)–C(18) | 121.10(17) |

| C(7)–C(8)–C(9) | 124.1(2) | C(17)–C(18)–C(19) | 121.29(17) |

| N(1)–C(9)–C(8) | 121.21(19) | N(2)–C(17)–C(18) | 121.80(17) |

| C(9)–N(1)–C(11) | 126.32(18) | C(16)–N(2)–C(17) | 121.95(16) |

| O(3)–N(3)–O(4) | 123.3(2) | O(3)–N(3)–C(22) | 118.33(18) |

| 3·CH2Cl2 | 5·0.5CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Distances | ||

| Fe(1)–O(1) | 1.918(3) | 1.925(6) |

| Fe (1)–O(2) | 1.900(3) | 1.877(7) |

| Fe (1)–N(1) | 2.063(3) | 2.068(8) |

| Fe (1)–N(2) | 2.109(3) | 2.060(7) |

| Fe (1)–Cl(1) | 2.208(12) | 2.229(3) |

| Bond Angles | ||

| O(1)–Fe(1)–N(2) | 157.26(13) | 159.5(3) |

| O(2)–Fe(1)–N(1) | 138.13(13) | 132.3(3) |

| O(1)–Fe(1)–O(2) | 93.21(12) | 92.4(3) |

| O(1)–Fe(1)–N(1) | 88.31(12) | 87.6(3) |

| O(2)–Fe(1)–N(2) | 86.69(12) | 87.7(3) |

| N(1)–Fe(1)–N(2) | 76.92(12) | 77.7(3) |

| O(1)–Fe(1)–Cl(1) | 101.80(10) | 101.4(2) |

| O(2)–Fe(1)–Cl(1) | 110.17(10) | 112.9(2) |

| N(1)–Fe(1)–Cl(1) | 110.41(10) | 113.7(2) |

| N(2)–Fe(1)–Cl(1) | 99.55(9) | 97.4(2) |

| Comp. | λ/nm (log ε) CH2Cl2 | λ/nm (log ε) DMSO | ΔE (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 301 (4.42) | 311(4.38) | +1068 |

| 349(4.22) | 357(3.04) | +642 | |

| 387(4.08) | 383(3.79) | −270 | |

| 446(3.51) | 420(4.12) | −1388 | |

| 453(3.20) | 466(3.22) | +616 | |

| 5 | 292(4.22) | 303(4.47) | +1243 |

| 375(3.90) | 392(4.34) | +1156 | |

| 435(3.95) | 447(3.54) | +617 | |

| 476(4.35) | 475(3.76) | −44 | |

| - | 502(3.48) | - | |

| - | 653(3.00) | - |

| 2 | 3·CH2Cl2 | 5·0.5CH3CN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Formula | C23H18FN3O4 | C23H16ClFFeN3O4·CH2Cl2 | C28H24ClFe2N2O3·0.5C2H3N |

| Formula mass, g·mol−1 | 419.40 | 593.61 | 604.17 |

| Collection T, K | 296 | 296 | 296 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | P | P21/c | Pbca |

| a (Å) | 6.50650(10) | 13.7047(8) | 17.1576(10) |

| b (Å) | 8.9928(2) | 7.3909(5) | 13.8793(10) |

| c (Å) | 17.7353(5) | 24.6860(14) | 23.1768(17) |

| α (°) | 98.3710(11) | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 92.8731(11) | 99.469(2) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 100.6470(10) | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 1005.82(4) | 2466.4(3) | 5519.2(7) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| Dcalcd (g·cm−3) | 1.385 | 1.599 | 1.454 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.347 × 0.284 × 0.176 | 0.281 × 0.129 × 0.068 | 0.143 × 0.114 × 0.096 |

| F(000) | 436.0 | 1204.0 | 2480.0 |

| Abs coeff (mm−1) | 0.103 | 0.981 | 1.182 |

| θ range (°) | 4.658 to 52.774 | 4.858 to 52.76 | 5.158 to 52.756 |

| Range h,k,l | −8/8, −11/11, −22/22 | −17/17, −9/9, −30/30 | −21/20, −17/17, −28/28 |

| No. total refl. | 25053 | 44081 | 98249 |

| No. unique refl. | 4116 | 5041 | 5616 |

| Comp. θmax (%) | 99 | 100 | 99.4 |

| Max/min transmission | 0.982/0.966 | 0.981/0.765 | 0.619/0.745 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 4116/0/270 | 5041/12/326 | 5616/0/326 |

| Final R [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0558; wR2 = 0.1550 | R1 = 0.0584; wR2 = 0.1487 | R1 = 0.1190; wR2 = 0.2982 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0735; wR2 = 0.1751 | R1 = 0.0852; wR2 = 0.1653 | R1 = 0.1473; wR2 = 0.3191 |

| Goodness of fit / F2 | 1.047 | 1.083 | 1.170 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole (eÅ−3) | 0.38/−0.32 | 0.56/−0.78 | 1.42/−0.97 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cisterna, J.; Artigas, V.; Fuentealba, M.; Hamon, P.; Manzur, C.; Hamon, J.-R.; Carrillo, D. Pentacoordinated Chloro-Iron(III) Complexes with Unsymmetrically Substituted N2O2 Quadridentate Schiff-Base Ligands: Syntheses, Structures, Magnetic and Redox Properties. Inorganics 2018, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010005

Cisterna J, Artigas V, Fuentealba M, Hamon P, Manzur C, Hamon J-R, Carrillo D. Pentacoordinated Chloro-Iron(III) Complexes with Unsymmetrically Substituted N2O2 Quadridentate Schiff-Base Ligands: Syntheses, Structures, Magnetic and Redox Properties. Inorganics. 2018; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCisterna, Jonathan, Vania Artigas, Mauricio Fuentealba, Paul Hamon, Carolina Manzur, Jean-René Hamon, and David Carrillo. 2018. "Pentacoordinated Chloro-Iron(III) Complexes with Unsymmetrically Substituted N2O2 Quadridentate Schiff-Base Ligands: Syntheses, Structures, Magnetic and Redox Properties" Inorganics 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010005

APA StyleCisterna, J., Artigas, V., Fuentealba, M., Hamon, P., Manzur, C., Hamon, J. -R., & Carrillo, D. (2018). Pentacoordinated Chloro-Iron(III) Complexes with Unsymmetrically Substituted N2O2 Quadridentate Schiff-Base Ligands: Syntheses, Structures, Magnetic and Redox Properties. Inorganics, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010005