Future Directions for Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Survey of the Existing Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets

2.1. Np3

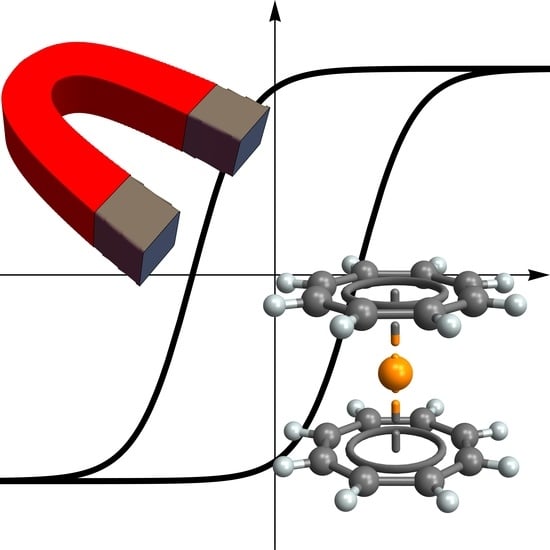

2.2. Np(COT)2

2.3. PuTp3

3. A Difficult Path Forward

3.1. Monometallic Complexes

3.2. Polymetallic Complexes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, S. Molecular Nanomagnets and Related Phenomena; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-662-45722-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sessoli, R.; Gatteschi, D.; Caneschi, A.; Novak, M.A. Magnetic bistability in a metal-ion cluster. Nature 1993, 365, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangregorio, C.; Ohm, T.; Paulsen, C.; Sessoli, R.; Gatteschi, D. Quantum Tunneling of the Magnetization in an Iron Cluster Nanomagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4645–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slageren, J.; Sessoli, R.; Gatteschi, D.; Smith, A.A.; Helliwell, M.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Cornia, A.; Barra, A.-L.; Jansen, A.G.M.; Rentschler, E.; et al. Magnetic Anisotropy of the Antiferromagnetic Ring [Cr8F8Piv16]. Chem. Eur. J. 2002, 8, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, P.; Carretta, S.; Amoretti, G.; Guidi, T.; Caciuffo, R.; Caneschi, A.; Rovai, D.; Qiu, Y.; Copley, J.R.D. Spin dynamics and tunneling of the Néel vector in the Fe10 magnetic wheel. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 184405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, O.; Carretta, S.; Santini, P.; Koch, R.; Jansen, A.G.M.; Amoretti, G.; Caciuffo, R.; Zhao, L.; Thompson, L.K. Quantum Magneto-Oscillations in a Supramolecular Mn(II)-[3 × 3] Grid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 096403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Chilton, N.F.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Zheng, Y.-Z. On Approaching the Limit of Molecular Magnetic Anisotropy: A Near-Perfect Pentagonal Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Molecule Magnet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16071–16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, C.A.P.; Ortu, F.; Reta, D.; Chilton, N.F.; Mills, D.P. Molecular magnetic hysteresis at 60 kelvin in dysprosocenium. Nature 2017, 548, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.L.; Dutkiewicz, M.S.; Walter, O. Organometallic Neptunium Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11460–11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocton, G.; Horeglad, P.; Pécaut, J.; Mazzanti, M. Polynuclear Cation-Cation Complexes of Pentavalent Uranyl: Relating Stability and Magnetic Properties to Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16633–16645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.L.; Jones, G.M.; Odoh, S.O.; Schreckenbach, G.; Magnani, N.; Love, J.B. Strongly coupled binuclear uranium–oxo complexes from uranyl oxo rearrangement and reductive silylation. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, S.G.; Ariciu, A.-M.; Kostopoulos, A.K.; Walsh, J.P.S.; Tuna, F. Molecular single-ion magnets based on lanthanides and actinides: Design considerations and new advances in the context of quantum technologies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 346, 216–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.D.; Long, J.R. Slow Magnetic Relaxation in a Trigonal Prismatic Uranium(III) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12558–12559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.M.; Tuna, F.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A.J.; McInnes, E.J.L.; Liddle, S.T. Single-Molecule Magnetism in a Single-Ion Triamidoamine Uranium(V) Terminal Mono-Oxo Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4921–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mougel, V.; Chatelain, L.; Pécaut, J.; Caciuffo, R.; Colineau, E.; Griveau, J.-C.; Mazzanti, M. Uranium and manganese assembled in a wheel-shaped nanoscale single-molecule magnet with high spin-reversal barrier. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mougel, V.; Chatelain, L.; Hermle, J.; Caciuffo, R.; Colineau, E.; Tuna, F.; Magnani, N.; de Geyer, A.; Pécaut, J.; Mazzanti, M. A Uranium-Based UO2+–Mn2+ Single-Chain Magnet Assembled trough Cation-Cation Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.L.; Hollis, E.; Nichol, G.S.; Love, J.B.; Griveau, J.-C.; Caciuffo, R.; Magnani, N.; Maron, L.; Castro, L.; Yahia, A.; et al. Oxo-Functionalization and Reduction of the Uranyl Ion through Lanthanide-Element Bond Homolysis: Synthetic, Structural, and Bonding Analysis of a Series of Singly Reduced Uranyl–Rare Earth 5f1-4fn Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3841–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, N. Spectroscopic and magnetic investigations of actinide-based nanomagnets. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2014, 114, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meihaus, K.R.; Long, J.R. Actinide-based single-molecule magnets. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2517–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddle, S.T.; van Slageren, J. Actinide single-molecule magnets. In Lanthanides and Actinides in Molecular Magnetism, 1st ed.; Layfield, R.A., Murugesu, M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; pp. 315–339. ISBN 9783527335268. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, N.; Colineau, E.; Eloirdi, R.; Griveau, J.-C.; Caciuffo, R.; Cornet, S.M.; May, I.; Sharrad, C.A.; Collison, D.; Winpenny, R.E.P. Superexchange coupling and slow magnetic relaxation in a transuranium polymetallic complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 197202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, N.; Apostolidis, C.; Morgenstern, A.; Colineau, E.; Griveau, J.-C.; Bolvin, H.; Walter, O.; Caciuffo, R. Magnetic memory effect in a transuranic mononuclear complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1696–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, N.; Colineau, E.; Griveau, J.-C.; Apostolidis, C.; Walter, O.; Caciuffo, R. A plutonium-based single-molecule magnet. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8171–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cornet, S.M.; Häller, L.J.L.; Sarsfield, M.J.; Collison, D.; Helliwell, M.; May, I.; Kaltsoyannis, N. Neptunium(VI) chain and neptunium(VI/V) mixed valence cluster complexes. Chem. Commun. 2009, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streitwieser, A., Jr.; Müller-Westerhoff, U. Bis(cyclooctatetraenyl)uranium (uranocene). A new class of sandwich complexes that utilize atomic f orbitals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karraker, D.G.; Stone, J.A.; Jones, E.R., Jr.; Edelstein, N. Bis(cyclooctatetraenyl)neptunium(IV) and bis(cyclooctatetraenyl)plutonium(IV). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 4841–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerridge, A. f-Orbital covalency in the actinocenes (An = Th–Cm): Multiconfigurational studies and topological analysis. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 12078–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.D.; Long, J.R. Slow magnetic relaxation in homoleptic trispyrazolylborate complexes of neodymium(III) and uranium(III). Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 13572–13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolidis, C.; Morgenstern, A.; Rebizant, J.; Kanellakopulos, B.; Walter, O.; Powietzka, B.; Karbowiak, M.; Reddmann, H.; Amberger, H.-D. Electronic Structures of Highly Symmetrical Compounds of f Elements 44 [1]. First Parametric Analysis of the Absorption Spectrum of a Molecular Compound of Tervalent Uranium: Tris[hydrotris(1-pyrazolyl)borato]uranium(III). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010, 636, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.D.; Long, J.R. Exploiting single-ion anisotropy in the design of f-element single-molecule magnets. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 2078–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, J.G.; Gingras, M.J.P. Magnitude of quantum effects in classical spin ices. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 144417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungur, L.; Chibotaru, L.F. Strategies toward High-Temperature Lanthanide-Based Single-Molecule Magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 10043–10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, F.; Mills, D.P.; Liddle, S.T.; van Slageren, J. The Inherent Single-Molecule Magnet Character of Trivalent Uranium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3430–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkiewicz, M.S.; Apostolidis, C.; Walter, O.; Arnold, P.L. Reduction chemistry of neptunium cyclopentadienide complexes: From structure to understanding. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kazzaz, Z.M.S.; Bagnall, K.W.; Brown, D.; Whittaker, B. Octathiocyanato- and octaselenocyanato-complexes of the tetravalent actinide elements. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1972, 2273–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P.L.; Dutkiewicz, M.S.; Zegke, M.; Walter, O.; Apostolidis, C.; Hollis, E.; Pécharman, A.-F.; Magnani, N.; Griveau, J.-C.; Colineau, E.; et al. Subtle Interactions and Electron Transfer between UIII, NpIII, or PuIII and Uranyl Mediated by the Oxo Group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12797–12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkiewicz, M.S.; Farnaby, J.H.; Apostolidis, C.; Colineau, E.; Walter, O.; Magnani, N.; Gardiner, M.G.; Love, J.B.; Kaltsoyannis, N.; Caciuffo, R.; et al. Organometallic neptunium(III) complexes. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copping, R.; Mougel, V.; Den Auwer, C.; Berthon, C.; Moisy, P.; Mazzanti, M. A Tetrameric neptunyl(V) cluster supported by a Schiff base ligand. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 10900–10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretta, S.; Amoretti, G.; Santini, P.; Mougel, V.; Mazzanti, M.; Gambarelli, S.; Colineau, E.; Caciuffo, R. Magnetic properties and chiral states of a trimetallic uranium complex. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2013, 25, 486001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mougel, V.; Horeglad, P.; Nocton, G.; Pécaut, J.; Mazzanti, M. Cation–Cation Complexes of Pentavalent Uranyl: From Disproportionation Intermediates to Stable Clusters. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 14365–14377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaunt, A.J.; Reilly, S.D.; Hayton, T.W.; Scott, B.L.; Neu, M.P. An entry route into non-aqueous plutonyl coordination chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1659–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmon, G.E.; Ling, J.; Unruh, D.K.; Moore-Shay, L.; Ward, M.; Weaver, B.; Burns, P.C. Uranyl−Peroxide Interactions Favor Nanocluster Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16648–16649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.-S.; Kaltsoyannis, N. High Spin Ground States in Matryoshka Actinide Nanoclusters: A Computational Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldoví, J.J.; Cardona-Serra, S.; Clemente-Juan, J.M.; Coronado, E.; Gaita-Ariño, A. Modeling the properties of uranium-based single ion magnets. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbowiak, M.; Rudowicz, C. Properties of uranium- and lanthanide-based single-ion magnets modelled by the complete and restricted Hamiltonian approach. Polyhedron 2015, 93, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, M.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Cramer, C.J.; de Graaf, C.; Gagliardi, L. Quantum Chemical Characterization of Single Molecule Magnets Based on Uranium. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magnani, N.; Caciuffo, R. Future Directions for Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets. Inorganics 2018, 6, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010026

Magnani N, Caciuffo R. Future Directions for Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets. Inorganics. 2018; 6(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagnani, Nicola, and Roberto Caciuffo. 2018. "Future Directions for Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets" Inorganics 6, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010026

APA StyleMagnani, N., & Caciuffo, R. (2018). Future Directions for Transuranic Single Molecule Magnets. Inorganics, 6(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics6010026